Anyone who’s paid any attention in the last few years to comedy or popular culture, in general, has noticed a couple of frequent sentiments: One is that people are so sensitive these days that no one can joke about anything anymore, and another is that kids these days have bad taste and are worthy of the contempt of their elders.

Kliph Nesteroff, America’s leading comedy historian, has dedicated his recent professional career to disproving both of those sentiments, mostly by pointing out that just about everyone, throughout history, has believed those things about comedy and young people. Nesteroff, on his popular social media account, often unearths old newspaper clippings of comedians decades ago having the same complaints as, say, Bill Maher today.

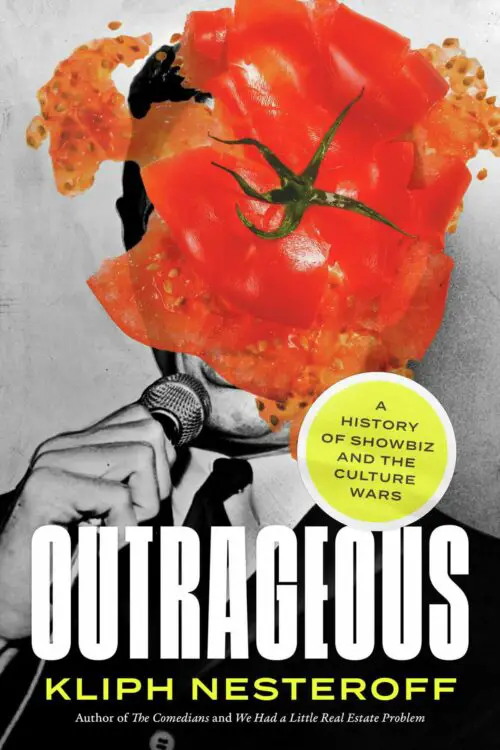

Now, Nesteroff has written a new book called Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars, which tackles all of these issues and more, in a series of stories from throughout the 20th century of controversial things, and the subsequent attempts to censor and subdue those things.

There are a few clear takeaways from the book: History frequently repeats itself. There’s probably less “cancel culture” now than in most phases of history. People freaked the hell out about things that weren’t worthy of such freak-outs ― like a sitcom character being pregnant, or The Simpsons. Pop culture figures, from Steve Allen to Bill Maher, will frequently be transgressive at one point in their career and a sanctimonious scold later on (and sometimes the other way around). And most of all, letters to the editor have traditionally been the province of insane people (the Internet comment section of the past).

I had the opportunity to speak to Kliph Nesteroff last month about the new book, and the many contradictions of cultural commentary today. This is part one; the second part will follow soon.

Stephen Silver: I’ve enjoyed your work for a couple of years. I’m not sure if I first saw you on Twitter, or when you did the Maron show, but I know I’m interested in the stuff you write about, and some of it is stuff I’ve written about myself. And I read your The Comedians book ― I had no idea how mobbed up the comedy world was, for the entire 20th century. That was kind of eye-opening.

Kliph Nesteroff: Yea yeah.

SS: Fascinating stuff, and the new book itself. So my first question is, how did you get into being a comedy historian? How did you land on that specialty, and what was your background that led you there?

KN: Well, it was accidental. I was doing stand-up comedy, beginning at the end of 1998, and I started doing it full-time in 1999. And like most people who are involved in comedy, you kind of start as a fan first. So like many other stand-ups, I knew I started collecting comedy records, as I found them in record stores and thrift stores. I started to become curious about some of these records that I was collecting because they were from a completely different era, many of them from the late ’50s/early ’60s, and many of the same comedians were ubiquitous, they’d be in every thrift store and every record store.

But, they were comedians I had never heard of, who I had never seen on TV. They were people with names like Woody Woodbury, Rusty Warren, Belle Barth, and Vaughn Meader, I’d see these records constantly in all the thrift store bins, and I was like, ‘Who is Vaughn Meader? Who is Woody Woodbury? Who is Rusty Warren? I never see them on any Best of The Ed Sullivan Show package, I never see them on the American Comedy Awards, any of the shows that I had watched growing up.

That led me to wonder, what was going on, who were these people, and the back covers of a lot of these comedy records that I’m buying said things like, ‘recorded in Miami Beach,’ ‘live from the such-and-such hotel in Miami Beach.’ Everything was Miami Beach, and I was like, what was going on in Miami Beach? And then, as the Internet became the Internet, suddenly there were more and more archival resources available to any layperson.

Google News used to have a thing called Google Newspapers, and they were one of the first online newspaper archives. Now, there are several other pay services like newspapers.com and Newspaperarchives.com. But back then, that was one of the only things, and one of the things they had in the archive was the Miami News, from the 1930s through the 1970s, so you could go through the entertainment listings, and find these listings for Woody Woodbury, and Rusty Warren.

So I inadvertently, accidentally, became a comedy historian just out of curiosity. But it was the comedy records, that were the gateway drug that led me down that path.

SS: Well one thing I noticed in the new book was that the more things change the more they stay the same. It’s like, it’s different things that people are fighting about, but it is, at the same time… and some of these letters to the editor. I know there are a lot of letters to the editor in there, I know it was the Internet comments section of its time.

KN: Yeah, exactly. Also, the most fun part, I think of the book, just showing people the indignancy that people had over the most innocuous things, whether it’s The Carol Burnett Show, or I Love Lucy, or Lassie, things that we would consider to be only family-friendly, people were apocalyptic about in those days. And of course today, on social media, people are as apocalyptic as ever about their pet hates, whether it’s the Barbie movie, whether it’s a stand-up comic.

And I wanted to just demonstrate that back in those days, people took those grievances seriously, they took themselves seriously, they truly believed that Elvis was going to corrupt the morals of youth, that The Beatles were the downfall of America or even more recent history, that The Simpsons was a bad example for children, that Beavis and Butt-head were going to lead to widespread arson. There was all this sort of fire and brimstone. We still have this fire and brimstone, but it almost feels like people take it even more seriously today.

So when people are really upset, and earnestly believe that Joe Biden is a Marxist Communist, or that drag queens are coming to recruit your children, the only position that a logical person could have is to laugh and ridicule it. Because even though there are concerning things in our culture, always, the sort of doomsday prophets are always wrong. And as decades pass, and you look back on those letters to the editor, they’re complaining about the Beatles, or Elvis or whatever ― it’s so funny, it comes across as so absurd. So why not today, do things not [come] across as funny and absurd, when they’re right in our face, because 10, 20, 30 years from now when we look back at it, all that hysteria is going to look ridiculous.

SS: I was shocked by that quote from Meredith Wilson. I always thought The Music Man was making fun of that sort of thing, with the pool table. But then here’s [the author of that play] talking about rock ’n’ roll…

KN: That quote, I don’t know if it’s clear in there, but that quote is from several years before he wrote The Music Man. I described him as Meredith Wilson, the composer of The Music Man because that’s what he’s best known for. But at the time of that quote, it was the early 1950s, he hadn’t written The Music Man yet. He had been a bandleader on radio, for the George Burns and Gracie Allen show, you’ll find his name in the credits…

But he hated rock ’n’ roll, Frank Sinatra at the time hated rock ’n’ roll. I think some of those people, turned later on as it became accepted, and part of the mainstream culture. Frank Sinatra, in his repertoire, would occasionally cover what would have been considered a rock ’n’ roll song… so I think a lot of those people mellowed out at the time, I think most people by this time have probably mellowed when it comes to rap music. But at some point, in the late ‘80s, and early ‘90s, everyone was hitting on rap music, saying it wasn’t music.

And that’s always what happens when there’s a new genre, it’s like ‘That was music, but this isn’t.’ And then, 20 years later it’s accepted as music. And the same with movies, same with crapping on the young, Millennials are a real scapegoat today, so it was in the ’50s when it was a teenage juvenile delinquency problem, and in the late ‘60s with hippies, and the latest ‘70s with punks… there’s always this sort of contempt for the young, as if culture and society were good until these young interlopers came along.