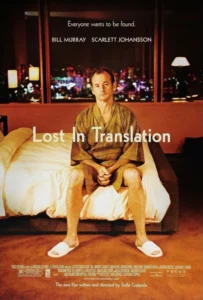

When it arrived in September of 2003, 20 years ago this month, Lost in Translation forever changed the careers of its three principals, writer/director Sofia Coppola and stars Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson.

Coppola had previously made her directorial debut with The Virgin Suicides — which was both well-received and a great, great movie — but Lost in Translation was her first major hit, and set off a great deal of speculation over whether it was really about her late marriage to director Spike Jonze.

For Johansson, it was both her first major adult role and a massive breakout for her. For Murray, it cemented his status, in that era of his career, as the go-to actor for sad middle-aged roles.

The Plot

The film is a lot more about atmosphere than plot, soundtracked with first-rate tunes by the band Air and composer Brian Reitzell, who also worked on The Virgin Suicides. Murray plays Bob Harris, a famous but fading actor who is in Tokyo to collect $2 million to shoot a commercial for a whiskey company. Depressed and in an unhappy marriage, he mopes about his fancy hotel.

That’s also the condition of Charlotte (Johansson), a 21-year-old recent college graduate who’s married to a famous photographer (Giovanni Ribisi), who’s shooting a rock band in Tokyo but doesn’t have much time for his wife (he seems to spend more time with a vapid movie star, played by Anna Faris – who was widely assumed to be imitating Cameron Diaz). So she, too, is doing little but moping around the hotel, and is introduced lounging on her bed, in the film’s famous opening unbroken shot of her ass:

The two soon form an attachment, which isn’t quite an affair but isn’t quite not an affair either. They get into some Tokyo adventures and open up to each other, and the film ends with him whispering in her ear:

While fans of the film have been trying for 20 years to suss out exactly what it is Murray says, I’ve long argued that we’re not meant to know. If we were supposed to hear what he says, it would have been clear and audible. Like most things in movies that are ambiguous, it’s left ambiguous for a reason.

Lost in Translation is a wonderful, beautiful film, which gorgeously photographed Tokyo and featured performances from both leads that are among their best work. It’s neck-and-neck with Virgin Suicides as the best of Coppola’s work.

Common Critiques

There are a couple of standard critiques of Lost in Translation that were made at the time and have been repeated over the years (a third one, the “age gap” one, luckily wasn’t such a thing in 2003). One of them is very valid, while the other is not.

The first is that the film has an Orientalist attitude towards Japan and Japanese people, and doesn’t grant a lot of agency or integrity to any of its Japanese characters.

This is undoubtedly true. The film’s Japanese characters are, essentially, a decoration, and/or something that happens to the American characters. Other than a friend of Charlotte’s who, I think, is named “Charlie,” none of them even have names. The same movie, if made now, would likely handle this better and not treat its Japanese characters so poorly.

The other critique is much less convincing. It’s the idea that the two main characters, one a famous movie star and the other a pretty and privileged girl, don’t really have anything to be so upset or depressed about. After all, what’s so sad about having to sit around at a fancy hotel in Tokyo? This tends to stand with the critique of Coppola as a nepotism case who’s particularly preoccupied with the problems of wealthy young white women.

This is nonsense. Anyone can be upset or depressed, no matter how outwardly full and happy their life appears to be, and it’s clearly established that both main characters aren’t particularly happy with the people they’re currently married to, which is the sort of thing that can make even rich and privileged people unhappy.

As for Coppola, you’re supposed to write what you know, and that’s what she does; subsequent films of hers like On the Rocks (also with Murray) appear also based in part on her own experiences, especially the part about having a famous father who’s known for being a horndog. And I always found Sofia Coppola’s career arc to be a refutation of what’s commonly claimed about “nepo babies”- nepotism got her a career (acting) that she was unqualified for and which she didn’t last in, but it also helped her get another career (directing) that she’s actually very good at, and has lasted in.

Lost in Translation, in every way besides its treatment of its Japanese characters, holds up well two decades later. It’s available to stream on Netflix.