[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ow do you go from a #1 hit and being one of the most successful so-called blue-eyed soul artists and considered the progenitor of power pop by ecstatic critics, to never really making a success story out of it, to a patchy solo career and odd-jobs, then back to being a producer and musical encyclopedia of rock and roll, to almost fully rehabilitating your career by the end?

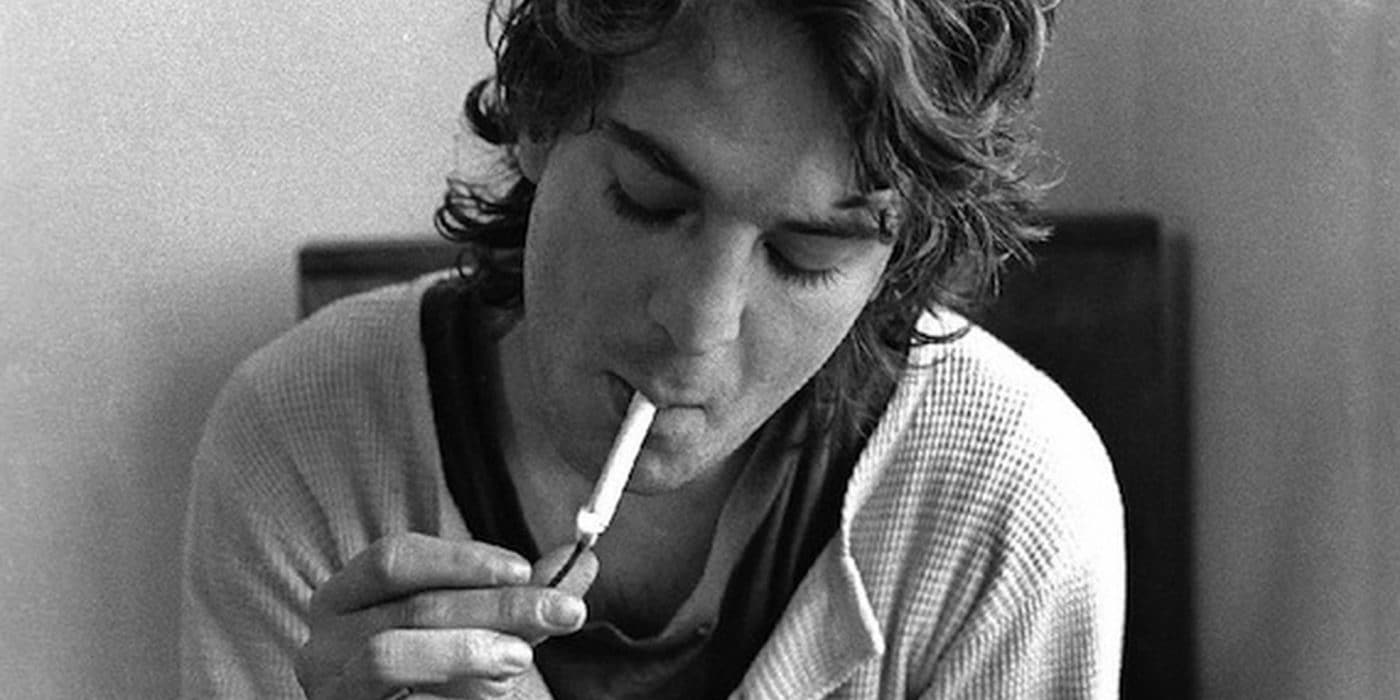

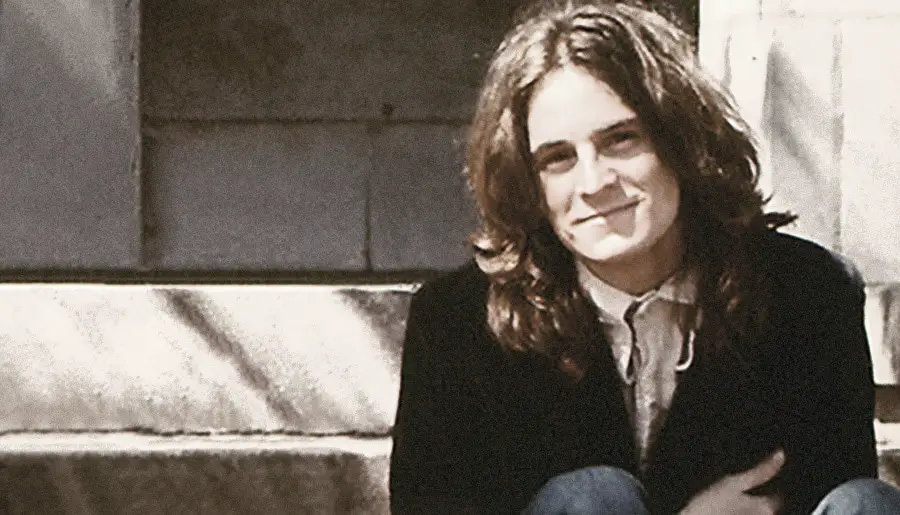

Well, you would have to ask Alex Chilton, the man from Memphis who went through all of that – that is, if he were still with us. He passed in 2010, leaving behind one of the more iconic and interesting musical careers you’ll ever find, full of hits, unfortunate misses, and strange and not so strange life stories. The closest you’ll get to hearing his life story straight from the source is with one of the best reads among musical biographies, aptly titled A Man Called Destruction (2014) by Holly George-Warren (named after an actual Chilton album from 1995), and the fantastic rock documentary, Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me (2012). However, recounting Chilton’s path through life is one thing and doing the same with his music is a another.

From A Star to “Big Star”

Ruth is Stranger Than Richard by Robert Wyatt is one of the weirdest albums of the ’70s (and on), has no true bearing on Chilton and his story, but it certainly has a fitting title concerning his life and musical career. In essence, the first question that can be posed is how did he become a star, seemingly out of the blue, and at only 16?

As Ms. George-Warren recounts it, it goes something like this – a young Alex gets discovered at high school gigs and talent shows in and around Memphis and gets noticed and connected with the brilliant production team of Chips Moman and Dan Penn. They pair him up with a local group, DeVilles, and get a recording contract as The Box Tops.

The first single, “The Letter”, clocking in at just under 2 minutes, hit #1 almost instantly everywhere, becoming one of the fastest number one hits ever. And its key characteristic was Chilton’s gruff voice; no listener was able to guess neither his race nor his age. And that’s where that ‘stranger’ element from the Wyatt album title already starts to figure in.

All he brought to the studio with him was a hangover and a sore throat.

Even at that early age, Chilton was known around Memphis as somebody who did whatever he wanted. The night before “The Letter” recording session, Chilton, and his then girlfriend got drunk and spent the whole night in a local cemetery on grass covered with dew. All he brought to the studio with him was a hangover and a sore throat. Combining the fact that he never recorded before, with the gruffness in his voice he managed to sing (properly) for about 90 seconds, so the producers added the airplane sounds at the end to get it as close to two minutes as they could.

Just like that, the accidental vocal became an instant hit. Along with the Dan Penn gem, “Cry Like A Baby”, and songs like “Cho Choo Train” and “Neon Rainbow.” Tasting success and learning from the best, like Dan Penn, Chilton wanted more.

…what would eventually become the Big Star rhythm section – Andy Hummel and Jody Stephens. What progressed from there was the story of the most influential, unsuccessful bands ever

This ‘more’ started to crop up with his first solo session in the early ’70s where he started covering and writing almost anything that could be labeled as good music. From the first versions of “Free Again” (later to crop up in the Big Star repertoire), to the Beatles-inspired “The EMI Song”, to the countrified “The Happy Song”, and even to his versions of world hits like “Jumping Jack Flash” and “Sugar, Sugar.”

All of that led to a friendship with Chris Bell, another musical prodigy, and his then band Icewater, that included what would eventually become the Big Star rhythm section – Andy Hummel and Jody Stephens. What progressed from there was the story of the most influential, unsuccessful bands ever.

“Dropout Boogie”

The first two (official) Big Star albums, #1 Record and Radio City are often proclaimed to be the first, and certainly among the most influential, power pop albums ever released.

Through Stephens’ connections, the band secured almost unlimited studio time at Ardent, one of the most renowned recording studios in Memphis. Which at the time ran its own record label as a Stax subsidiary. Big Star became its first, and was supposed to be its key act. Having the freedom to practically do anything in the studio they wished, Chilton and Bell, and later on Chilton (almost) by himself, came up with some amazing, critically acclaimed music.

The first two (official) Big Star albums, #1 Record and Radio City are often proclaimed to be the first, and certainly among the most influential, power pop albums ever released. Just by saying two names – Cheap Trick and The Cars, two bands that made it big by being influenced by Chilton and the band, is enough. But, you can add to that, Chilton’s songs from the second album that became items of deep reverence for quite a few indie bands. “What’s Going Ahn”, “Mod Lang”, and particularly “September Gurls”, inspired not only bands but entire genres and record labels.

Then what happened? Unless you count the ecstatic reception from music critics, nothing at all (they didn’t reach cult status until much later). The albums came and went without much fanfare or mainstream success. A big part of the problem lay in the financial troubles Stax ran into at that time; being bought by Columbia, who didn’t care much about either Ardent label or Big Star, led to ridiculous distribution, and non-existent promotion.

“Everybody goes, leaving those

Who fall behind

Everybody goes, as far as they can

They don’t just care

You’re a wasted face, you’re a sad-eyed lie

You’re a holocaust”– “Holocaust” 3rd/Sister Lovers

Chris Bell left after the first album, and when Radio City went nowhere, Chilton, with his wild spirit and drug addictions, started becoming disillusioned. Following, what him and the band came up with is probably one of the saddest rock albums in existence, alternatively called 3rd and Sister Lovers (him and Jody Stephens were dating twin sisters at the time). It was yet another album that inspired a whole genre and label(s) – ‘sadcore’ and the 4AD label sound were practically built on it. To this day, it is one of those albums that has had numerous official and unofficial reissues.

And that’s where Chilton began dancing to the tune of one of Captain Beefheart’s early signature songs – “Dropout Boogie.” Columbia refused to release his next project, but it did appear in its first form in 1975 as a semi-bootleg, nobody really sure what the song order was, or for that matter, which songs should be included.

Things Usually Get Worse Before They Get Better

From then on Chilton went into a downward spiral. Well, somewhat. Moving to New York and getting attracted to punk/new wave and the whole CBGB scene, Chilton slowly started turning to something he obviously considered to be of ‘true rock values’, slowly becoming something of a rock and roll archivist.

Through a series of patch albums and EP’s, some with a higher level of quality (Like Flies on Sherbet (1979)), and some not so much (Singer Not The Song), Chilton went back to his pre-Big Star mode – everything (musical) but the kitchen sink.

…his music, much like his life, is certainly an unfinished story.

As the Big Star cult reputation, and along with it, Chilton’s started to grow, nothing remotely resembling success was approaching, and Chilton’s lifestyle certainly didn’t help. Moving to New Orleans in the ’80s, Chilton started picking up odd jobs from dish washing to tree cutting, before eventually returning to music.

He once again covered almost everything – from the bluesy psychobilly of Tav Falco & Panther Burns (for whom he both played and was the producer of), to using a jazz horn section on some of his own recordings.

As his reputation steadily grew over time (The Bangles scored it big with their version of “September Gurls”), he even got a song devoted to him – “Alex Chilton” was The Replacements tribute to the guy.

“And the children by the million sing for Alex Chilton

When he comes ’round

They sing, “I’m In Love”

What’s that song

Yeah, I’m in Love

With that song”– The Replacements “Alex Chilton”

The true revival of Chilton’s musical credibility began in the ’90s when he revived Big Star with The Posies’ main duo, Auer/Stringfellow. While it gained momentum when “In The Street” from #1 Record became the theme music for That 70’s Show. But then, Chilton seemed to get fed up with everything, doing enough music just to get by.

When hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Chilton stayed in the house where he lived at the time and had to eventually be rescued by a helicopter. And in mid-March 2010 Chilton went to a New Orleans hospital, where he died of a heart attack.

Championed for a long time by the likes of R.E.M. and others, Chilton’s and Big Star’s music has only recently been getting a true re-assessment. In particular, with the release of a number of box sets and complete 3rd album sets. However, his music, much like his life, is certainly an unfinished story. Something Chilton himself would probably appreciate. Maybe.