The ongoing Hollywood Writers’ strike has reached its fourth week, and many people, especially those who are not responsible for content, are asking themselves, “What’s all this fuss?” Let’s start off by saying this: “Welcome to Hollywood, everyone!” In many people’s eyes, this place might seem always sunny in the morning, shallow in the afternoon, glittering at night, and easy to live in. Well, that’s a hard no for many insiders.

In case you are wondering, this is not a piece about the star system, the easy life, or the people who aren’t responsible for the above-mentioned content; this is actually a peek inside the lives of many writers who crowd tiny apartments, noisy coffee shops and, in some unfortunate circumstances, their parents’ houses still. It might be a long one, but stick with me anyway, as we can draw a timeline of the Writers’ strikes across the years in order to acknowledge them as the insiders who have gone on strike more than any group in Hollywood.

To begin with, did you ever ask yourself why we have unions? Let’s put it this way, if you’re doing really well working for someone in the industry, and you’re not in a union, well, God bless you son, because you belong to a rare species! Unfortunately, the real world works differently, and unions are established in order to look after workers’ needs and creative rights, at any given time in their careers. The fundamental principle of these organizations is that unity is strength.

Strike One, Strike Two, and More

Writers have gone on strike eight times in more than 70 years, which is more than any other group in Hollywood has done so far. The current strike is the first in 15 years. That’s why it might be a good idea to address this topic right now: Why did it take so long to get back on the streets against capitalist interests? Well, this narrative might be interpreted as a cyclical one, so why don’t we look into previous writers’ strikes in order to identify some patterns:

1953

The Screen Writers Guild (SWG), a predecessor of the Writers Guild of America (WGA), went on strike for 13 weeks. This led them to obtain the first residuals for reuse from television products, with payments for up to 5 reruns; sequel payments in television for creators of original works, control of credits in television, and minimum pay. So far so good, but let’s move on…

1960

The WGA struck the The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) for 22-weeks, eventually winning the right to receive residuals for the showing of theatrical films on free television. They also obtained a 4% residual for television reruns. In addition, these radical changes in the contracts included an independent pension fund and participation in an industry health insurance plan. So here, we begin to see how labor rights can be obtainable, especially during technological advancements, by these professionals.

1973

Changes in the entertainment industry, often driven by technological advancements, have presented each generation of union members with new challenges and opportunities to make their needs heard. That’s why writers went on strike for 112 days, obtaining salary increases as well as residual payments for movies shown on VHS and pay television, anticipating the future appearance of these means of distribution. Once again, technology drives the change while begging for new regulations. The writers reasonably took advantage of it.

1981

A strike lasted 96 days resulted in the contract that for the first time guaranteed writers a share of producers’ revenues from the fast-growing pay television and home video markets. The strike idled many entertainment industry workers, whereas writers’ gains included new terms for reuse of television programs on newborn cable channels, shifting from fixed residuals to better percentages on the distributor’s gross receipts.

1985

Writers approved a new pact after a two-week strike, but the union were forced to accept a formula for home video residuals based on 0.3% of distributors gross. In this circumstance, the president of the Union said he was unhappy with the deal, as the share was too little compared to the new producers’ cut destined to the writers. It took only 3 years to get back on strike…

1988

The WGA struck the AMPTP for 22 weeks, the longest strike in its history. The strike forced layoffs at many studios and brought financial hardship to thousands of industry workers. Talks collapsed several times, with studios threatening to concentrate on producing work with non-union scripts. Eventually, the writers obtained new contracts with new formulas for calculating residuals, increases in minimum pay, better cuts on international sales, and improvements in creative rights for the writers of original screenplays and television shows.

2007-08

Prior to this strike, the WGA had no arrangement with producers regarding the use of content online. It took a 100-day strike to reach a substantial agreement for the opposing sides: a new contract gave writers a stake in the revenue when their movies, television shows and other creative content was distributed on the internet. The strike prompted networks and studios to order new unscripted programming and accelerate the return of other shows to ride this new wave and invest on sequels.

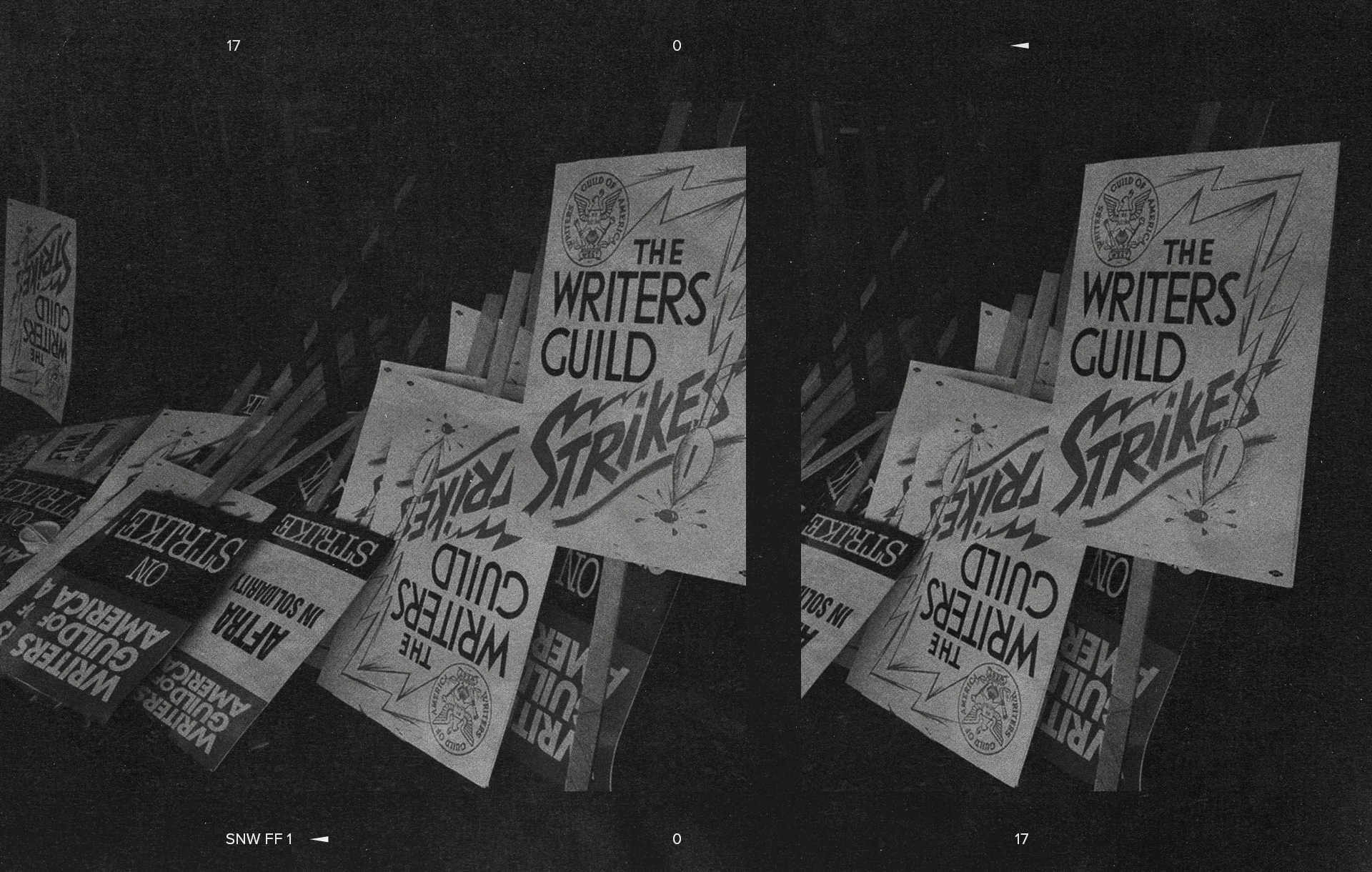

2023

Here we are, it’s May 2, 2023, and the WGA announces a strike after a last ditch effort at negotiating a new contract with AMPTP. The main focus point in the labor dispute is the residuals from streaming platforms, which are difficult to measure in this redefined marketplace. The series and films remain on the platforms for a very long time and do not have to be periodically acquired (generating a fee for the authors) as happened in the past. Also, because of the high demand of scripted shows, writers rooms become smaller and fast-paced. So, in this context, writers demand a minimum number in the writers’ room and the guarantee of being employed for longer periods. The strike is still ongoing.

Today: A New Day, a New Way

All the battles that the WGA has gone through are a good indicator of the grit and tempering of this organization, whose sole objective has always been to preserve and defend these professionals’ creative rights and salary expectations based on continuous economic and technological transformations. Without these professionals, Hollywood wouldn’t have a single story to project or broadcast on its screens.

Speaking of technological transformations, this is probably the most powerful force driving the industry towards profit today. Writers never argued that these changes aren’t necessary, especially if such changes gain the approval of the new audiences that are more prone to stay at home and watch something on a streaming platform rather than going out. Yet, this cannot represent a threat either, as content is still king, and writers must be defended if we want more of it on those platforms.

No wonder Hollywood writers are very concerned that artificial intelligence will be used to replace them in the next few years. In the current negotiations, they are also aiming to impose some limitations on artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, and how it will be used in the industry: they would prefer to look at it as a tool that could help with research or facilitate script ideas. However, in front of these concerns, the studios offered just an “annual meeting to discuss advancements in technology,” the WGA said. This is one of the main reasons why the strike is still on.