When rock music journalism started to flourish in the second half of the ’60s, it also became a trend for music journalists, particularly in England, to do their best to come up with some humor. Some of those jokes and puns were really good, while some… widely missed the mark. One of those such puns was the name a number of English journalists gave to the music coming out of then West Germany in the late ’60s and early ’70s: Krautrock.

The joke was supposed to be a play on the fact that supposedly all Germans love sauerkraut, food that is not exactly to the taste of many people elsewhere. This pejorative term, which missed its mark in many ways, actually stuck and now designates such a wide array of musical styles. Even coming to be applied to a number of artists that don’t even come from Germany or the European continent, and is now also the subject of quite a few detailed academic studies.

As FactMag once put it, “it’s odd that a now-accepted genre has been graced with such a one-dimensional name, especially given the depth and breadth of krautrock’s varied musical offerings.”

What lies behind?

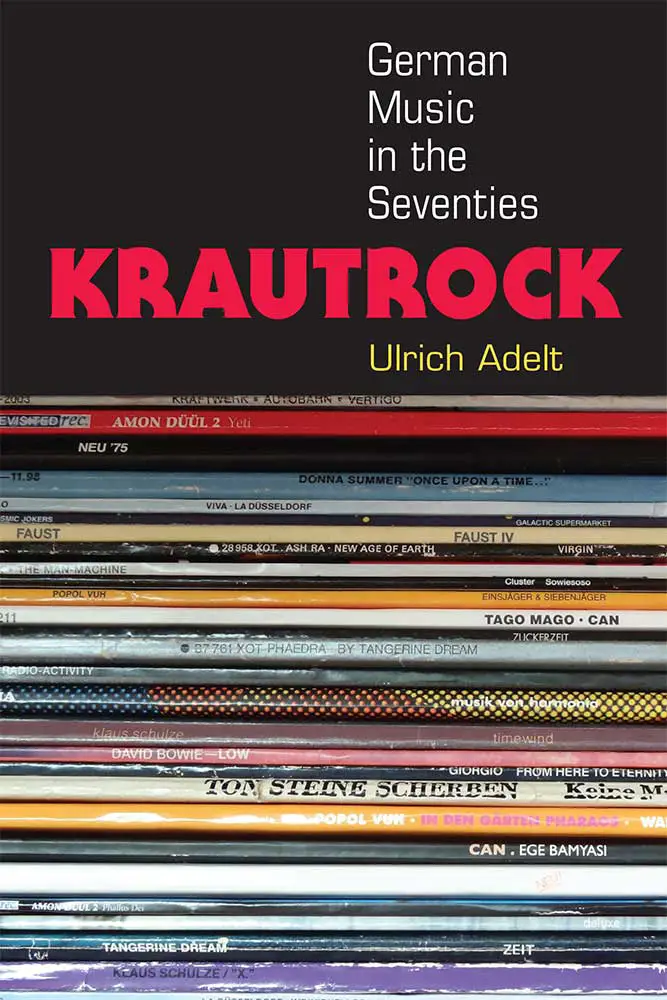

As those academic studies go, all of them tried to define what Krautrock actually signifies, and one of the most comprehensive comes from Ulrich Adelt, Associate Professor for American Studies and African American and Diaspora Studies, at the University of Wyoming in his work Krautrock – German Music In The Seventies, where he says the following:

“Krautrock is a catch-all term for the music of various white German rock groups of the 1970s that blended influences of African American and Anglo-American music with the experimental and electronic music of European composers. Groups such as CAN, Popol Vuh, Faust, and Tangerine Dream arose out of the German student movement of 1968 and connected leftist political activism with experimental rock music and, later, electronic sounds.”

Adelt very much hits the mark there. In its beginnings, Krautrock was certainly not one single definitive music genre but encompassed a number of different artists in big West German cities of Munich, Hamburg, Cologne, and a bit later Berlin that had one common idea in their mind: move away from the established pop and rock forms of the time and to paraphrase one leftist thinker, “experiment, experiment, experiment.”

Move away from the established pop and rock forms of the time and to paraphrase one leftist thinker, “experiment, experiment, experiment”

Both consciously and subconsciously, these German artists also wanted to use their music/art as a way to move away from the dark legacy and the role Germany played in World War II; many of the most prominent (and not so prominent) Krautrock artists preferring leftist-oriented ideas that dominated that era.

So, what was their starting musical point, or to be more precise, musical points? Artists like Amon Düül collective (later split into Amon Duul and Amon Düül II) took the starting point of more experimental rockers at the time like Mothers of Invention and Pink Floyd, but including modern European classical music, like that of German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and jazz, particularly it’s avant-garde part.

From Experimental Psych to Trailblazing Electronics

As Gary Bearman points out, “what free jazz did for traditional jazz in the ’60’s, krautrock did for rock in the ’70’s. While psychedelic groups broke boundaries, krautrock groups annihilated them. Good krautrock at its best completely dismantles normal structure or seriously warps structure or at least piles so many sound effects upon the normal structure as to make more traditional rock music somewhat unrecognizable. Also, the Germans were not only pioneers of electronic music, but the first to really effectively incorporate highly synthesized sounds into rock music.”

He further details why the ‘Krautrock sound’ is so diverse and musically hard to put a finger on:

“There’s the more simplistic, driving beats and electronics of Neu!, the more complex rhythms and experimentation of CAN, the more grandiose and progressive sound of Amon Duul II, the guitar freakouts of Guru Guru and Ash Ra Tempel and the all-out wild experimentations of Faust. There’s the more contemplative world music of Popol Vuh, the lower key electronics of Cluster, the more aggressive electronics of Kraftwerk, the space rock and synthesizer experimentations of Tangerine Dream & Klaus Schulze, the jazziness of Embryo, the warped folk of Holderlins and the Eastern-tinged complex rock of Agitation Free.”

Germans were not only pioneers of electronic music, but the first to really effectively incorporate highly synthesized sounds into rock

In his big piece on the subject in now-defunct music weekly Melody Maker, Simon Reynolds notes that “tweaking … Anglo-American legacy, the German bands added a vital distance (coming to rock’n’roll as an alien import, they were able to make it even more alien), and they infused it with a German character that’s instantly audible but hard to tag.”

“A combination of Dada, LSD, and Zen resulted in dry absurdist humor that could range from zany tomfoolery to a sort of sublime nonchalance, a lightheaded but never lighthearted ease of spirit. Although they occasionally dipped their toes into psychedelia’s dark side (the madness that claimed psychonauts such as Syd Barrett, Roky Erikson, or Moby Grape’s Skip Spence), what’s striking about most Krautrock is how affirmative it is, even at its most demented. This peculiar serene joy and aura of pantheistic celebration are nowhere more evident than in the peak work of CAN, Faust and Neu!”

Key Reference Points: CAN, Faust, Neu! Kraftwerk

CAN started out as a combination of musicians that began as students of Stockhausen’s music (keyboardist Irmin Schmidt and bassist Hoger Czukay), jazz (drummer Javi Leibezeit) ‘rocker’ (guitarist Michael Karoli), and outwardly singers in Michael Mooney (their first album) and one street singer, Damo Suzuki (their best albums).

As Reynolds notes, CAN was the funkiest and most improvisational of all the Krautrock bands. Recording in their own studio in a Cologne castle, they jammed all day, then edited the juiciest chunks of improv into coherent compositions. This was similar to the methodology used by Miles Davis and producer Teo Macero. As CAN’s resident Macero, Czukay deployed two-track recording and a handful of mics to achieve wonders of proto-ambient spatiality, shaming today’s lo-fi bands.

The name that is most stuck in the minds of listeners is Kraftwerk

If anything is seen (and heard) as Krautrock these days, it is the so-called ‘motorik’, the kind of perpetual, propulsive hypno-groove of Neu!. Based mainly on the musical ideas of drummer Klaus Dinger and highly inventive guitarist Michael Rother (who keeps on producing some incredible solo recordings).

Neu! Produced some of the most rhythmically inventive compositions that often moved into the realm of ambient soundscapes as a counterpart to the electronic ambiance created by the likes of Popol Vuh (who did the soundtracks for Werner Herzog’s best films) or Tangerine Dream.

It seems that only now, artists elsewhere are fully exploring Neu!’s inventions. If many German artists, at the time, were not too happy with the Krautrock tag, Faust, one of the most experimental music collectives in rock history, embraced it with a good dose of humor and a pinch of salt. After all, they used the Krautrock title for one of their most accomplished compositions, when they decided to do a composition as such.

As Reynolds aptly puts it, Faust oscillated wildly between filthy, fucked-up noise and gorgeous pastoral melody, between yowling antics and exquisitely-sculpted sonic objets d’art. Above all, Faust were maestros of incongruity; their albums are riddled with jarring juxtapositions and startling jump cuts between styles.

Yet, the name that is most stuck in the minds of listeners is Kraftwerk, the band that can easily be taken as the creators of modern electro music from electro dance to all forms of techno and house and everything in-between.

Ralf Hunter and Florian Schneider, the band’s original masterminds, picked op on Stockhausen’s electronic experiments, added minimalist classical music of John Cage and Steve Reich and turned it into something completely new, creating at least five genres of modern electronic pop music themselves.

Krautrock Then and Now

While during its prime Krautrock was essentially limited to a cult status audience, rock critics and a number of hip musicians (David Bowie, Brian Eno, Robert Fripp, Iggy Pop), its wider acceptance only grew through time.

In the ’80s, artists like The Gang of Four and The Fall started developing various ideas of Krautrock artists, possibly culminating in Talking Heads masterpiece Remain In Light.

The full-blown influence of Krautrock possibly came in the ’90s, from photo-bunkers like Pavement, motorik exponents like Stereolab to ambient and post-rock exponents that are quite abundant these days. Today, as David Stubbs points out, “[w]henever a new group wish to show their experimental credentials, they will reach up and pick out the word ‘Krautrock’ like a condiment to add a radical dash to their press release.”