* Slight Spoilers Ahead *

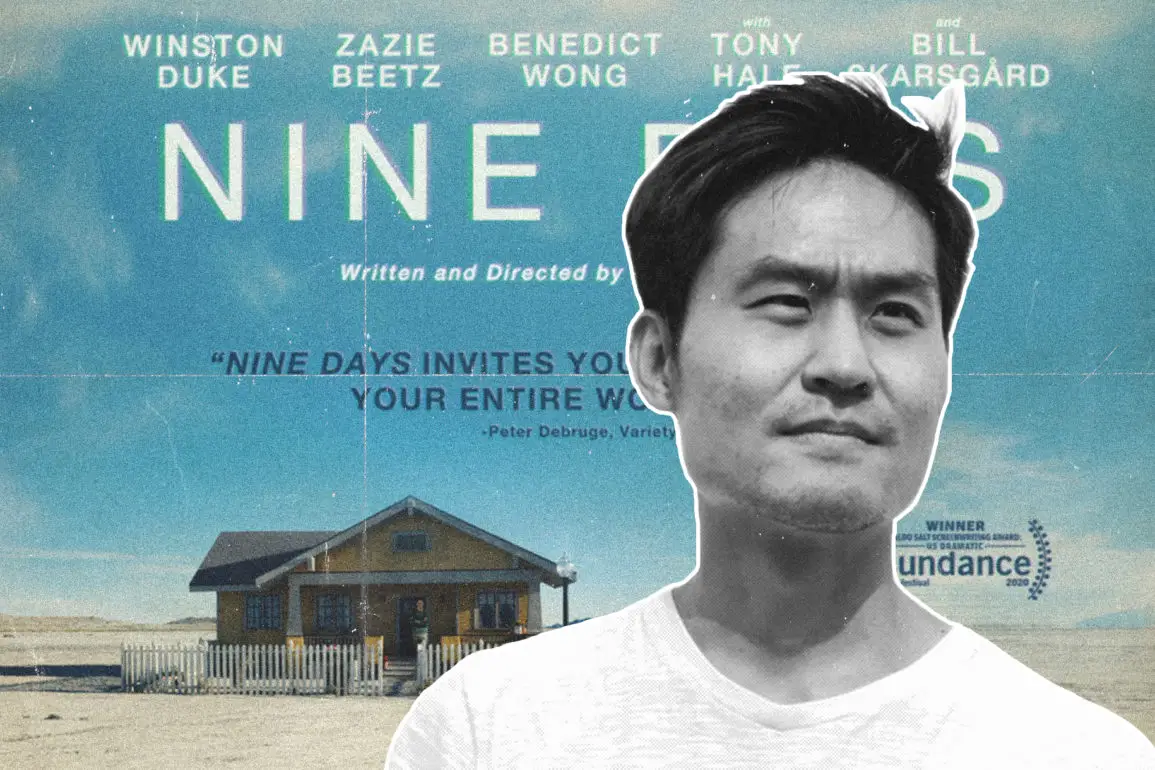

Brazilian native Edson Oda’s feature directorial debut, Nine Days, is about a man’s (Winston Duke) soulful search for the meaning of life, death, and their place among a harsh, unforgiving world. Equal parts visually dazzling and auditorily enhancing, the film is fittingly executive produced by one of Oda’s main filmmaking inspirations, Spike Jonze, and boasts the same re-recording mixer as A Quiet Place and A Quiet Place Part II, Brandon Proctor. In fact, the talent behind Nine Days is immense, with a supporting cast including Benedict Wong, Zazie Beetz, Tony Hale, and Bill Skarsgård, serving as a testament to Oda’s strong script.

On the eve of Nine Days‘ release, I had the opportunity to speak with Oda about the inspiration behind its metaphysical story, working with Duke and his fellow Marvel actors, Wong, Beetz, and Skarsgård, the “surrealness” of collaborating with Jonze, his filmmaking inspirations, and more.

When writing Nine Days, was there a certain part of the world you wanted to find meaning in?

It’s interesting because I didn’t go that far, trying to find the meaning . For me, it was more like I wanted to write something that felt personal, but there’s no pretension in terms of how this movie has to answer this or that question for me. It came more from my need to write rather than just a result oriented action.

A need to create, which also resonates with the film’s themes. It begins with a beautiful succession of vignettes and faded memories of Amanda’s life. And it invoked in nostalgic feeling in me. Why did you choose VHS tapes and old TVs to capture this?

It’s interesting because I grew up with VHS. For me, it was just part of what represents the past. So choosing VHS would have this nostalgic feeling, as I would see in the VHS and also the tube TVs. And I knew it would be weird to see this very nostalgic world being represented by iPads and Macintoshes, or stuff like that. And then I gave some kind of motif to that because I knew, visually, it would be more interesting. But for me, I felt like Will, when he died, he got imprisoned in this time. So there is no technology from after he passed away. So that’s more or less the reason that we just see those old things, not very technological ones.

And the house at the end of this lifeless, yet visually captivating desert is not an unfamiliar image of the afterlife. Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek, among other ancient mythologies, involve a variation of this. What was your inspiration for this remote house?

For the desert, it was more a story need. I needed a place which would be isolated, and at the same time would be very different from the world we live in. I needed separation for things that you see – the TVs – in this world. And it felt like a desert would be the way to go because he’s isolated. We see how his size is reduced to a minimum. And at the same time, I didn’t want to be too fantastical or too sci-fi-ish, but I wanted it to be something that you could see in the real world. So it’s very grounded. So if I think of anything that I can see in the real world that would translate it, a desert would be that.

Winston Duke has such a dominating screen presence.

Yeah. He’s great.

Yet his performance is so tender, tepid, and sensitive. It almost levels his imposing stature, adding to, like you said, the already minimizing of his character with the setting. What were your conversations like surrounding this character and the thematic elements?

We started with how you feel when you hurt in life. there is a lot of things that make you feel less and make you hurt and make you somehow not want to live, or not want you feel anything. And I had a bunch of conversations, especially with the main character. Will was an uncle of mine who committed suicide, and also my connection with him and my feelings of empathy, after, when I grew older, and just trying to understand how he felt. And also feeling things that he felt, as well. First, we even started seeing pictures of him and just telling some stories of him and seeing some drawings and this kind of stuff. And it was interesting because, first thing, Winston was, “This guy was so full of life. He was so handsome.” And he liked to see him like that, which was very interesting.

And then, later, it was a lot about having conversations about life and about things that we go through – even different kinds of depressions, as well. So we went very deep in those conversations. And it was interesting how Winston really embraced the character, almost like he was sacrificing part of him while he was going deeper into the character in the scene. So it was amazing to see his performance. But at same time, I was almost feeling guilty for making him go to those places. But he really wanted to go to those places, and in the performance you see on the screen, you can see that he was he was very committed, and it was very real.

It might be his finest performance to date. I was blown away. Will is desperate for human connection, even though he doesn’t always show it. And Emma, Zazie Beetz’s character, sees through his process. She knows he’s still hurting, and they have a unique connection. Do you see a path forward for each of them in a different life?

I have my interpretations, but it’s more like I’m not right or wrong. It’s just my interpretation. It’s interesting. Some of my favorite movies let you fill the gaps. Even when it was coming to a conclusion, and when it was going towards the end, II think that’s what happened, but I don’t know everything about this. I’m not the god of the work that I create. I am more like, “Okay, I put the pieces together,” but after that, their characters create the rest. So there’s no final, ultimate meaning. It’s more about you watching. It’s like life. When someone dies, you can come up with your own or interpretation for where we come from and all this stuff.

Why Emma’s character, out of all the other characters? What made her dig deep into Will?

It’s interesting because all the characters are some part of who I am, somehow. And Emma is more like, sometimes, the exasperation, as it’s almost like there’s a more evolved being. And she has this goodness within her in a sense of she’s aware of herself, and she has her own desires and goals and thoughts and everything, But also, she’s so selfless in some ways as someone who sees the other people and not just herself. And, from that, she is the one who was able to see Will rather than just wanting something from him. And that’s what makes her able to just like, “Okay. I can see this person went through some pain.” And she’s interested about this guy, and somehow she wants to understand where he’s coming from and empathize with him, and that’s where this relationship comes from.

But I think it’s hard for Winston, too, because the world is not like that. The world is so goal oriented, and so much about surviving that I don’t judge Will for just wanting to send someone else. If the world was different, somehow, for sure he would say, “Okay, I can send her.” But he was afraid and with reason. “Can I send her? Can she survive here?” He’s not [the biggest] Kane fan, but he thinks to himself, “Yeah, this guy is going to survive.”

Because Kane seems to be the toughest.

Yeah.

In a lot of ways, this film is about recognizing talent and coping with unrecognized talent in a world that increasingly disregards creativity and kindness. Is this at the root of Will’s odyssey?

Actually, it’s not why. It’s more he was just trying to figure out if she did it. And it’s interesting because some people just see the scene are like, “Oh yeah, she did it.” But then some people don’t think the same way. For him, it was difficult because he didn’t see any signs. Or he saw the signs, but he just didn’t know that that she was like him, somehow. And rather than just trying to find reasons, it was more like trying to find a conclusion on did he fail when he chose her or not? So it’s more like if she committed suicide. But then when he figured out that’s what happened, he said, “Oh, okay. So she went through the same thing that I did, as much as I suffer. And I failed because I shouldn’t put someone in a world that would go through that.” So it was more like the connection of, “Was this person like me? And if this person was like me, I failed because I was a failure.” So that was his psyche behind it.

Right. And that line in her letter, “My soul was born without an immune system.”

Oh, you read it. Oh, interesting.

Yeah. It’s a really powerful phrase. If Will knew from the beginning that she did it, would he have chose her?

No. If he knew she was like him, I don’t think he would. But it’s more my perception because for him, what hurt him most was, it wasn’t like she failed, or anything. It was more like she went through the same pain he went through. And for him, that was his responsibility. He put her in the world and made her suffer like he suffers. And, for him, suffering that way is worse than being alive at all. But after the end of the movie, possibly, he could consider choosing her again.

Yeah, because Emma might have given him a new perspective.

Right. A different perspective because he wasn’t a failure, and she wasn’t a failure.

Emma, along with Kyo, Benedict Wong’s character, remind him that, sometimes you don’t need to create for other people. Creating for yourself is enough to fulfill.

Yeah. That’s a great way to see it.

And Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is so perfect for your story. How did you choose it?

Dead Poets Society. There is a scene that I love which was they talk about “Yawp, Yawp.” It’s interesting because we don’t have the familiarity with Walt Whitman because I’m from Brazil. I never heard about him. And for me, when I was watching Dead Poets Society, I said, “Wow, this is really cool.” So in the end, I knew he would perform something like a monologue, but I didn’t know exactly what it was. And then I remember the energy of the “Yawp,” and I said, “Okay, let me take a look at it.” And “Song of Myself” is exactly that poem of the “Yawp,” but without that part because it’s super long, and then we just edited it in a way that would fit in four or five minutes.

And it’s so wonderful to finally see Will open up. Speaking of the cast, it features some of the finest actors working today.

I agree.

Including four Marvel actors. How were you able to obtain a cast like this for your first feature?

It’s funny, when I was talking to them, I didn’t even think it was like, “Marvel,” which was funny, but it was pretty much writing a script and having my producers and my reps just love the script. And they connected to it on a very deep level. They really connected to it for the same reasons I connected to it. I wrote the script, and they were really touched by it. And then we just started sending it out. And I just did shorts, I didn’t have any features under my belt. No one knew who I was, but, somehow, when a lot of them read the script, they just felt, “Okay, I understand where he’s coming from.” So this was a very vulnerable piece, very personal. People just started relating to it and seeing themselves in it. The meetings were pretty much like these kinds of conversations – just talk about life and things and struggles. It came from that vulnerable place that we all share.

You mentioned Dead Poets Society. What are some of your other filmmaking inspirations?

For this, Spike Jonze was a huge influence for me. He became one of the executive producers of the film. It was surreal to see that. It is interesting because in his movies, there’s so much grounded realities that somehow are a little weird in the way they’re not a 100% real, but they feel so real and so grounded. And that’s with real emotions and real characters. And that’s something that always inspired me. And then there is Terrence Malik, in terms of the visual feelings. And (Hirokazu) Koreeda, the Japanese director, is just amazing – how he captures emotions. My favorite movie of his is Like Father, Like Son, but I do like the movie called After Life, which some people see as almost a sequel of Nine Days, which is kind of cool. Michel Gondry. There’s something interesting about his practicality [with] visual effects in a way to create this very theatrical environment. And very handmade. There’s not very much of his style, but Quentin Tarantino is someone who I admire.

Speaking of practical effects, it was expertly used. When writing this script, how much did you want to use practical effects versus CGI?

I always wanted (practical). I come from advertising. And I was a big fan of Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry’s work, especially because he was always very theatrical. And Georges Méliès. I really love this feeling of the filmmakers as magicians. They do it in front of you. Even when you’re filming, you’re feeling that magic somehow. So, for me, it was something from the beginning, even when I was having conversations about the TVs, one of my requirements was like, “Yeah, all the TVs would be have to be practical. We can’t CGI. We have to just be on set with all the TVs,” and then later learning [that] would be a nightmare, so we did a hybrid. But everything else like projections and experiences, it was important for me to find a way to make it feel (like) everything was there. And it’s part of the personality of the movie. You almost feel like this is all happening there while they’re going through this process. So it was very important for me.

Do you have any other projects that you’re working on or that you’re concocting?

Nothing very concrete, I’m writing something. It’s like a personal project. I don’t want it to be that big, but small and intimate, and somehow be something I can see, chronologically as my second Nine Days. Everything now is just like I need to focus on my writing, and let’s see what comes from that.

NINE DAYS OPENS IN THEATERS IN NEW YORK & LOS ANGELES JULY 30, 2021, FOLLOWED BY NATIONWIDE EXPANSION AUGUST 6, 2021