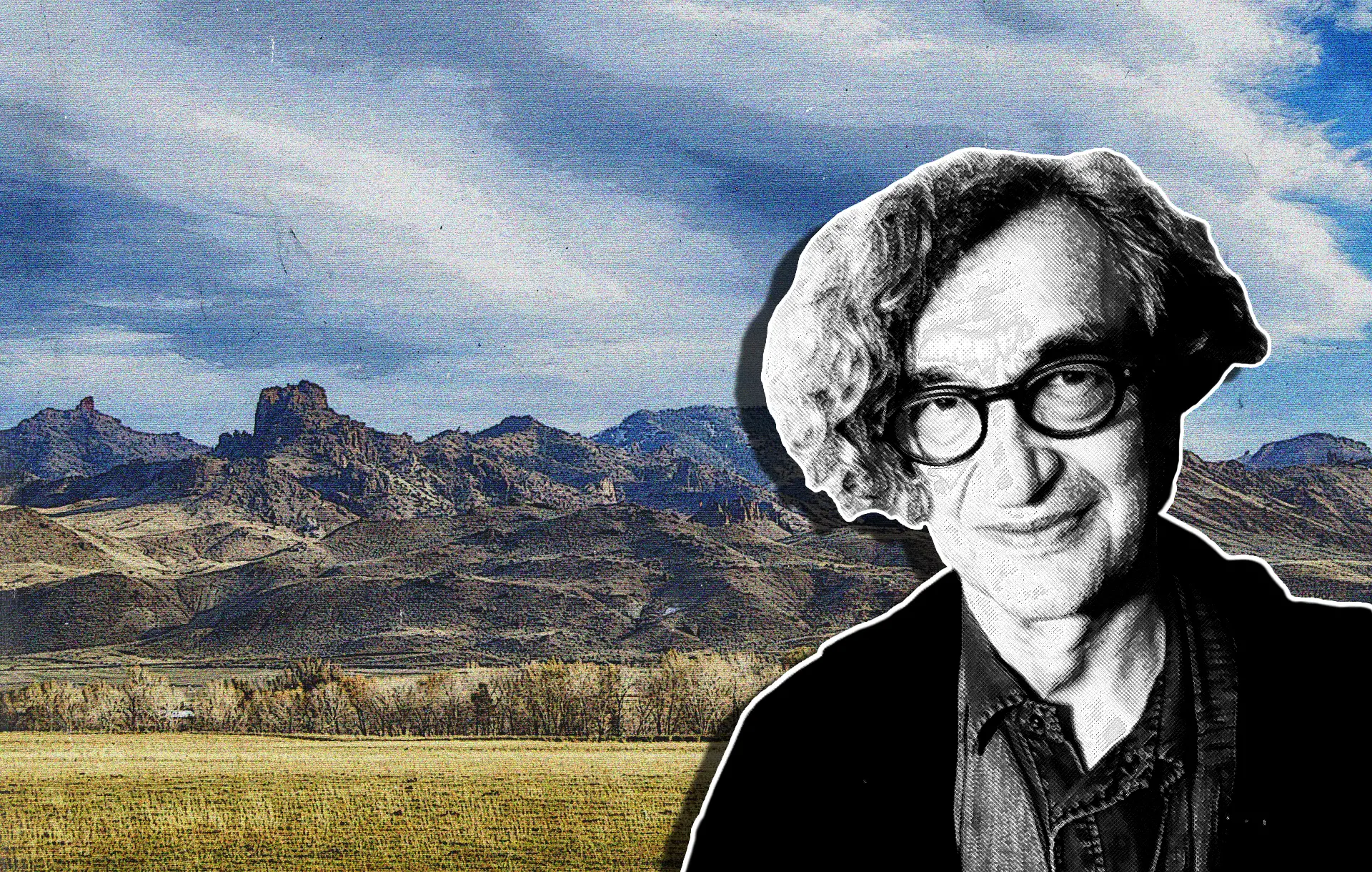

Alice in the Cities (1974) begins with its protagonist in North Carolina where he’s doing a work report on living life on the road in America. Due to his sheer stubbornness to do things his way–by taking Polaroids instead of penning words–the man gets fired by his publisher. I couldn’t find a more representative image to describe German filmmaker Wim Wenders and his fascination with the iconic wild landscapes of the American West, which made up a good part of his childhood’s imagery and sensitivity.

To emphasize this concept and its centrality within his filmography, Wenders did exactly the same thing in 1983 when looking for subjects, locations, and people that would bring the desolate landscape of the American West to life for his magnum opus, Paris, Texas (1984). He simply took his own camera on the road and never stopped using it. As the antithesis of the doom and gloom of his childhood home (Düsseldorf), the man was captivated by the saturated colors and the unparalleled emptiness of these magnificent landscapes. This is how this artist realized that the landscape could play a more central role in his films; serving as a character of its own.

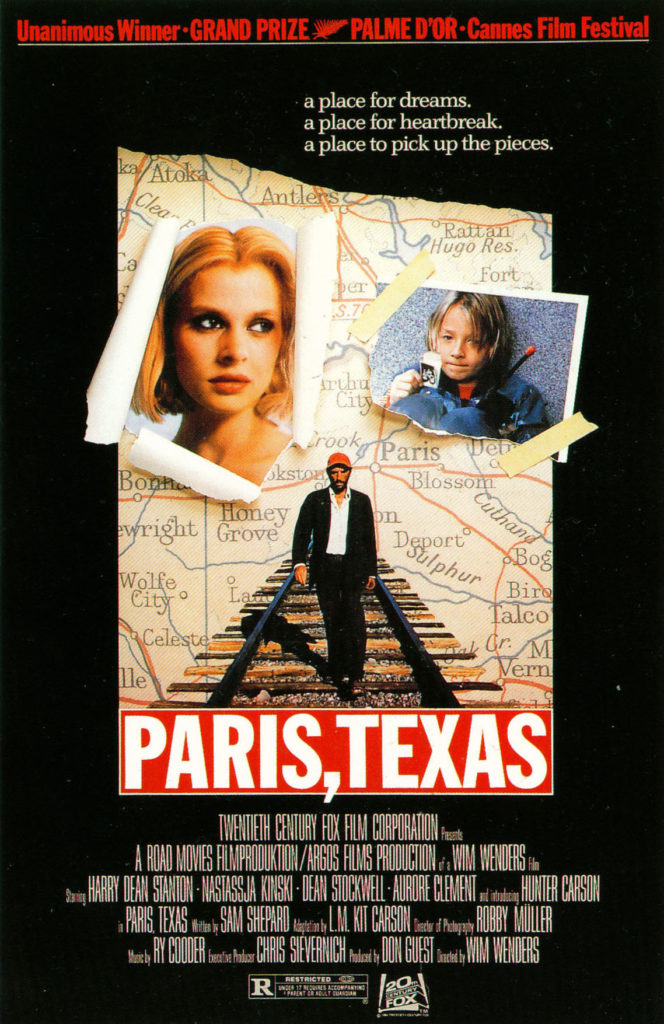

At the 1984’s Cannes Film Festival, Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas bagged the most prestigious awards including the Palme d’Or, the FIPRESCI Prize, and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. This visually stunning film, which leans far more on the New German Cinema’s approach to filmmaking rather than the bombastic and glossy American one, is still held in great consideration by countless American cinematography professors for its unique take on what America looks like in the eyes of an eloquent observer from the Old Continent. As an exploration of the inner world of its hero rather than outer conflicts that he might stumble upon, this film somehow depicts the contemporary sense of alienation that many artists strive to exhibit in their work.

The German Way

If there is one European movement that’s made history for its complexity and for its often-dark atmospheres, this would certainly be the New German Cinema. From its beginnings, with directors such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Berlin Alexanderplatz) and Werner Herzog (Aguirre, The Wrath of God, Nosferatu the Vampire, Fitzcarraldo), this movement certainly did not write its guidelines by experimenting with comedies. Among the most famous directors of this tradition, there is one who has also built a bridge between Germany and the United States. Most would consider these two dimensions antithetical in many aspects yet they are united by the same sense of vastness and abandonment before his own eyes.

Wenders has in fact created a new German aesthetic within this movement by drawing its strength from that sense of post-war desolation

Hailing from a country with a difficult post-war experience, ideologically fragmented, and constantly divided between that sense of guilt and melancholy, Wim Wenders still managed to become one of the greatest filmmakers and storytellers of our time. His ability to communicate the depth of the human condition is the direct consequence of his childhood fascination with the American Western, which is nothing but the canvas of his masterpieces. In contrast with the post-war ruins of his hometown, their broad, sweeping landscapes and existential sense of disorientation are vividly imprinted on his films which are often, as he explains, “extrapolations of Westerns into the present day.”

Wenders has in fact created a new German aesthetic within this movement by drawing its strength from that sense of post-war desolation that has divided Germany into two factions, culturally invaded by the United States, and yet able to recreate its own new identity. In Wenders’ films there is a sense of melancholy and devastation that, despite the strength of a memory so unspeakable for its gravity, as Nazism, manages to translate into poetic and symbolic images such as the dance on the trapeze in Wings of Desire (1987), a film inspired by art depicting angels visible around West Berlin at the time it was encircled by the Berlin Wall.

A Bridge Over Diverging Waters

Wenders’ America is lyrical and unique. The story flows from room to room, from a corner of a vast landscape to another, with no abrupt breaks. The photography interacts with the austere spaces of this magnificent country, using the American vastness as an empty yet brilliant canvas and the German gloom as the best destination for two angels whose sole raison d’être is, as one of them says in the film, to “assemble, testify, preserve” reality.

Behind their silent aesthetics, the director reveals a pictorial sensibility, which rejects any advertising aesthetics, managing to make everything that is framed beautiful, even the waste. Therefore, he manages to express intense atmospheres, poised with dreamy sequences such as in the case of a videotape showing fleeting moments of happiness from the past in Paris, Texas.

In the end, Wim Wenders has managed to become the symbol of this newfound conjunction between Western America and the Old Continent and, thanks to his works, we can appreciate American films from a completely new perspective. He basically steals those magnificent sceneries and then enriches them with a new soul, a delicate intimacy, and their untold contradictions – no wonder he chose the juxtaposition between Paris and Texas. Do not get me wrong, this artist is not a critic of today’s America. He can rather be looked at as an illegitimate son, who wants to do anything in his power to grab the attention of his corpulent and proudly boisterous mother.