As vast as the film industry can be, Hollywood’s still a small community where, despite the many eccentricities that the star system provides, the weirdest things keep happening right off the pre-production stages. One of these strange occurrences is the phenomenon of “twin films.” This term refers to two or more feature films holding significantly similar plots and subject matters that get released within a few weeks from each another.

The more audiences questioned themselves about the origin of this phenomenon, the more they found themselves in agreement that it could generate from different factors. For instance, working as a story analyst for a well-known production company, I realized that the same screenplays are sent to several film studios before being accepted, and that one can be a reason why executives from different studios are constantly updated on potentially buzz-worthy titles.

This term refers to two or more feature films holding significantly similar plots and subject matters

The movement of personnel between studios can also be a reason behind such phenomenon. Then, if we want to believe in good faith and ignore the possibility of an industrial espionage theory, a possible explanation could be found in the case of big events — such as a terrorist attack — that occurred not too long before the release, or even significant anniversaries resulting in multiple interpretations of the same subject matter. But that’s not the case of the infamous anecdote featuring Douglas McGrath and executive producer Bingham Ray, told by the latter to the New Yorker.

An Infamous Anecdote

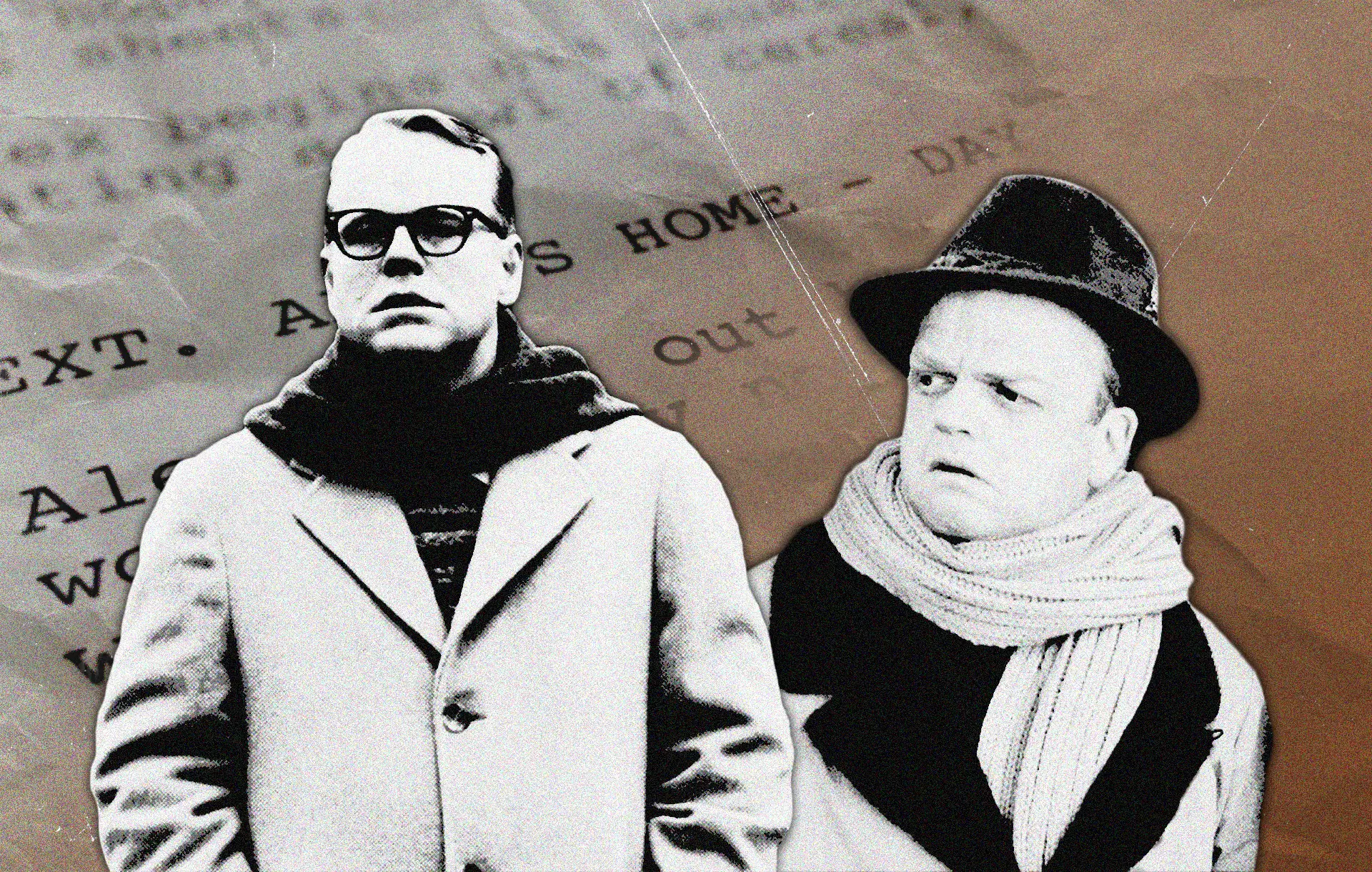

When Douglas McGrath finished writing Infamous (2006), a screenplay about the life of Truman Capote, he couldn’t believe what he finally achieved. It took two years of his life, since the research had been an excruciating process. Upon accomplishing the work, he did what he had promised to do: he called his friend Bingham Ray, who was the executive on his last film, Nicholas Nickleby (2002), and gave him the good news.

However, when McGrath reached out, he found out that his friend had another Capote script on his desk. Bewildered, Ray told the New Yorker that the script, by Dan Futterman, covered the same period in Capote’s life that McGrath’s work covered. “It’s very strange,” McGrath said, “I mean, what are the chances of two scripts about Truman Capote going out at the same time?”

Futterman’s Capote (2005) wound up getting made first, and was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards

Well, to resolve McGrath’s dilemma, we could take a closer look at so many notable examples covering a span of time that goes from 1934 with The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934) and The Scarlet Empress (1934) — both about Catherine the Great, to the more recent cases of The Darkest Hour (2017) and Dunkirk (2017) — which both addresses Britain’s dramatic rescue of troops from the French coast in May 1940. As we can see, twin films are as old as the film industry itself.

Getting back to the Capote twins, Futterman’s Capote (2005) wound up getting made first, and was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards while its star, Philip Seymour Hoffman, won the Oscar and Bafta Best Actor prizes for his impersonation of Capote. Infamous, with the unknown British actor Toby Jones in the lead role, went into production a few months after Capote, and it turned out to be a box office bomb.

Plausibility of the Industrial Espionage Theory

If we consider that Capote and Infamous were inevitably compared by reviewers and audiences, with Capote generally agreed to be the better of the two (also by virtue of it releasing earlier), then the industrial espionage theory comes naturally to us. Otherwise, what’s the meaning of releasing a title with the same subject matter with such a sense of urgency and so close to the other one?

On the other hand, it should be kept in mind that executives, assistants, and interns from different studios have always socialized (that’s inevitable), and production schedules are almost public domain in some cases, especially nowadays, with teasers posted on social networks at the earliest opportunity in order to punch up a specific concept and stimulate the hype around it.

At this point, the only possible conclusion is that sometimes Hollywood releases similar films in a short span of time by coincidence while, other times, a studio finds out about another studio’s project and wants to match them. In that case, both studios hurry to get their film out first, such as the case of Capote and Infamous. But why? Well, according to Mark Hughes, screenwriter and Forbes film critic, this might be a case of both studios knowing that the idea is good but only one can be a hit, or it could be that they are counting on the critical acclaim of one to help the other.