Who can be named among the greatest jazz musicians/composers of all time, and at that, among the greatest musicians/composers of music as such?

The list can be extensive, but if you narrow it down, a few stand out. Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus… you can add a few other names there, but one certainly belongs up there at the top with the above-mentioned, and that is Thelonious Sphere Monk.

As his official website, aptly notes, he is “recognized as one of the most inventive pianists of any musical genre, Monk achieved a startlingly original sound that even his most devoted followers have been unable to successfully imitate. His musical vision was both ahead of its time and deeply rooted in tradition.” Simply put, he was not just one of the greatest American composers, but one of the greatest composers of modern music. Period.

No wonder he was given quite a few nicknames – “Melodious,” “The Mad Monk,” “The High Priest of Bebop,” or “The Genius of Modern Music.” Looking at his artistic output from the current perspective, the reasons for most of these are quite clear, he is certainly one of the geniuses of modern music, many consider him the father of bebop jazz, and his piano playing style was certainly melodious.

Yet the mad monk one might seem incongruous with the rest and can come from the fact that he was often misunderstood while he was still around composing and playing. You see, Thelonious Monk was a true original in every aspect of his life, “his commitment to originality in all aspects of life—in fashion, in his creative use of language and economy of words, in his biting humor, even in the way he danced away from the piano—has led fans and detractors alike to call him ‘eccentric,’ ‘mad’ or even ‘taciturn.'”

The Spheres Align

No, Sphere was not Monk’s nickname. It was his second given name, as he was born on October 10, 1917, in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Monk was four years old when most of his family (mother and two sisters moved to New York).

At a very young age it turned out that Thelonious was a musical prodigy. He started out playing the trumpet but turned to piano already at the age of nine. Even in his early teens, he was already playing at parties, at a local Baptist church and at that age he won several amateur hour competitions at the Apollo Theater.

Although he was both a good student and athlete too, Monk quit high school during his Sophomore year to pursue music. In 1935 he became a pianist for a traveling evangelist and faith healer.

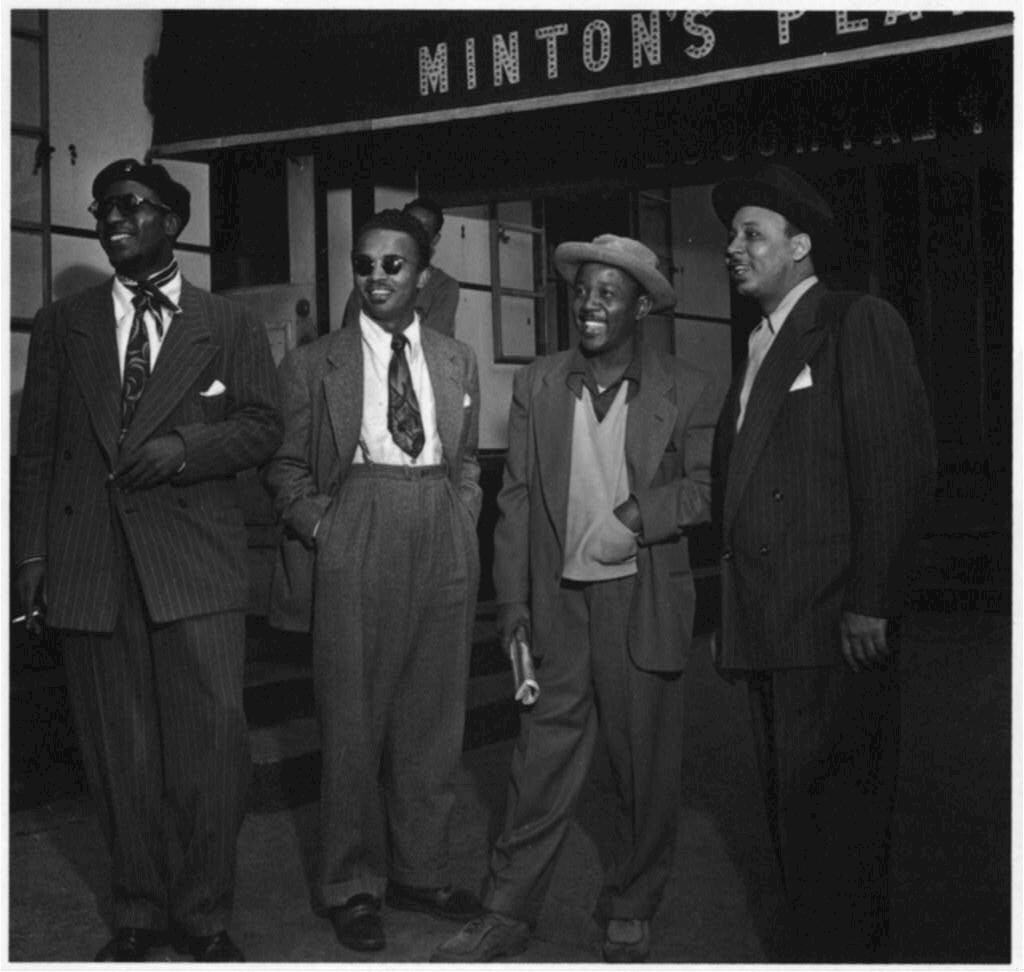

Two years on, he decided to return to New York to form his own quartet. For four years his group played local bars and small clubs when in 1941 well-known drummer Kenny Clarke hired Monk to be the house pianist at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem. And that is when Monk’s legends started rolling.

The Man Behind the ‘Bebop Revolution’

It seems that his stint at Minton’s gave birth to one of Monk’s nicknames, “The High Priest of Bebop.” During that time he started coming up with his ever-evolving harmonic innovations. These innovations were not only fundamental to the development of jazz at that time, but their importance remains among the most crucial ones even today.

Some of the compositions he came up with at the time, like “52nd Street Theme,” “Round Midnight,” “Epistrophy” are certainly among his best, and best in jazz history. “Round Midnight” is probably one of the compositions that define modern jazz the most.

That is why it is said that Monk not only ushered in the bebop, but at the same time “charted a new course for modern music few were willing to follow.” As the text on his site explains, “most pianists of the bebop era played sparse chords in the left hand and emphasized fast, even eighth and sixteenth notes in the right hand, Monk combined an active right hand with an equally active left hand, fusing stride and angular rhythms that utilized the entire keyboard. And in an era when fast, dense, virtuosic solos were the order of the day, Monk was famous for his use of space and silence.”

Essentially, Monk was creating a completely new setup in music, “in which harmony and rhythm melded seamlessly with the melody.” As he explained himself at one point, “everything I play is different. different melody, different harmony, different structure. Each piece is different from the other. . . . [w]hen the song tells a story when it gets a certain sound, then it’s through . . . completed.”

Recordings Begin

Monk’s first official recordings came through his engagement with saxophone great Coleman Hawkins (1944). The initial response among critics and musicians was actually quite hostile. Still, Blue Note, which was only a fledgling label at the time, gave Monk the opportunity to record his first session as a leader in 1947, at the time when he was already 30 years old and practically a veteran on the jazz scene.

From the current vantage point, all of Monk’s recordings for Blue Note are now considered classic and rank among his best, but at that time they practically had no commercial success.

What didn’t help Monk and his reputation was the fact that in 1951 he was arrested for narcotics possession. It turned out that he took that rap to save his friend and fellow jazz piano legend, Bud Powell. What complicated Monk’s situation further was that the arrest deprived Monk of his so-called cabaret card, meaning that he couldn’t play any gigs in New York for six years.

Monk used that period (1952-1954) to record for Prestige label and play outside NYC. These sessions included another set of excellent performances including those with Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, and Milt Jackson. During that period Monk played in Europe and also recorded his first solo piano album in France.

After Prestige, in 1955 Monk moved to the Riverside label, recording some of the albums that garnered critical acclaim, including Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington, The Unique Thelonious Monk, Brilliant Corners, Monk’s Music, and his second solo album, Thelonious Monk Alone.

Baroness Pannonica Steps In

At some point (1957), Monk got help from his sometime patron and friend the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter. She helped Monk get his cabaret card back. Monk returned the favor by coming up with “Pannonica,” one of his better-known compositions.

His stints at renowned New York clubs that included his work with John Coltrane and other renowned jazz musicians brought Monk to Columbia records (1962). This recording deal was followed by the fact that in 1964 he became the third jazz musician in history to grace the cover of Time Magazine.

Yet that cover also came along with media stories about his behavior, more than his music. Time itself called him the “loneliest Monk,” helping paint the picture of him as “the reclusive, naïve, idiot savant whose musical ideas were supposed to be entirely intuitive rather than the product of intensive study, knowledge, and practice.”

His former sideman, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, explained: “If Monk isn’t working he isn’t on the scene. Monk stays home. He goes away and rests.”

Even though Monk recorded some stellar albums for Columbia/CBS (Criss Cross, Monk’s Dream, It’s Monk Time, Straight No Chaser, Underground), the label quietly dropped Monk from its roster in 1972.

Monk compensated for the loss of the recording deal by touring with the “Giants of Jazz,” a fantastic jazz showcase that included bass greats like Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Al McKibbon, and Art Blakey.

His last public appearance was in 1976 since due to “physical illness, fatigue, and perhaps sheer creative exhaustion convinced Monk to give up playing altogether. On February 5, 1982, he suffered a stroke and never regained consciousness; twelve days later, on February 17th, he died.”

The decades that passed only confirmed that Thelonious Monk is a true genius not only of jazz but of modern music. Some recently uncovered live recordings, like the one with John Coltrane, or solo in Palo Alto only confirm that fact.