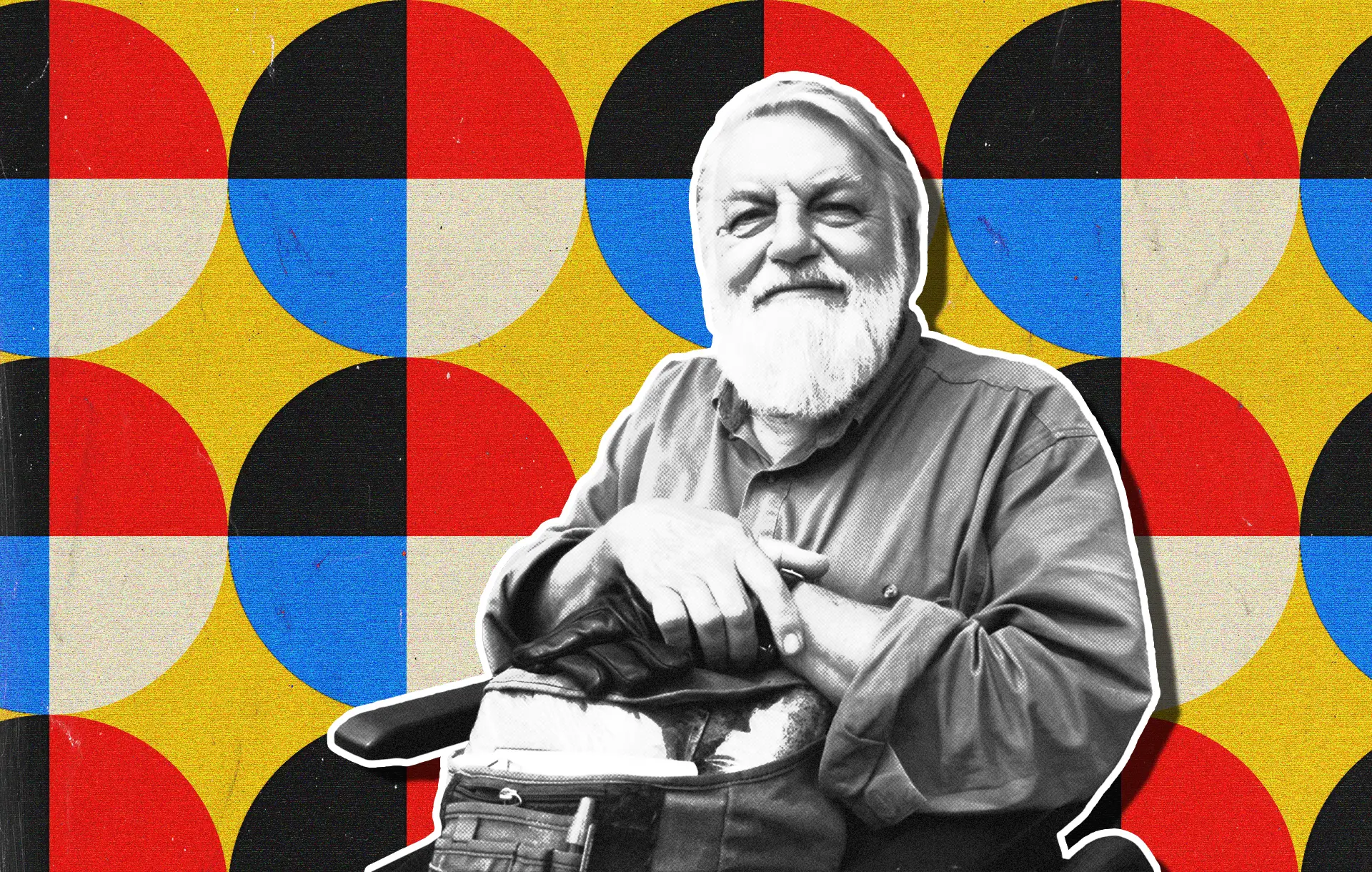

Sometime in 2014, Robert Wyatt, with more than 40 years in music decided to officially retire from creating it. Maybe he just got tired. Maybe it was his poor health. Maybe both. He himself said that it was his age and greater interest in politics. “There is a pride in stopping, I don’t want the music to go off.”

But, whatever the reason is, he leaves behind a musical legacy that seems to have the strongest impression on musicians themselves — particularly in his native Britain. Even considering that he didn’t have a lot of singles breaking onto the British charts. Maybe it was exactly his left-oriented politics and his very direct presentation of political views, through music or otherwise.

He leaves behind a musical legacy that seems to have the strongest impression on musicians themselves

Still, the legacy is there, and his influence on music creators who see no point in genre boundaries nor repressing their views on social and political issues is undeniable. So much so that in January 2015, Wyatt’s biography Different Every Time was featured as BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week, abridged by Katrin Williams and read by Julian Rhind-Tutt.

So, what is the story of Robert Wyatt? A man whom many consider to be “a key player during the formative years of British jazz fusion, psychedelia and progressive rock.” A man who created music that crossed countless boundaries and whom one music journalist dubbed ‘the saddest voice in modern music?’

Can you have a ‘soft machine?’

For the fans of progressive rock music, the term ‘Canterbury scene’ has an almost mythical significance. Some of the earliest and later on, some of the best prog artists originated in this English university town. Canterbury sound actually became an-all around term describing a specific sound carried on even by artists who actually had no formal connections with the city itself. Actually, Canterbury was exactly the place where Wyatt began his musical career and was one of the artists that heavily influenced the so-called Canterbury sound.

He started by playing drums, tutored by a visiting American drummer George Neidorf. He spent time with Neidorf in Majorca, Spain (1962), but decided to return to England joining a group formed by Daevid Allen, who later became a prog-rock legend for his solo work and Gong, one of the seminal prog bands.

When Allen left for France to form Gong, Wyatt and Hugh Hopper (one of his band members) formed a ‘true psych’ band, Wilde Flowers, where they were joined by another duo of later prominent prog artists — Kevin Ayers and Richard Sinclair (the leader of archetypal Canterbury sound band Caravan).

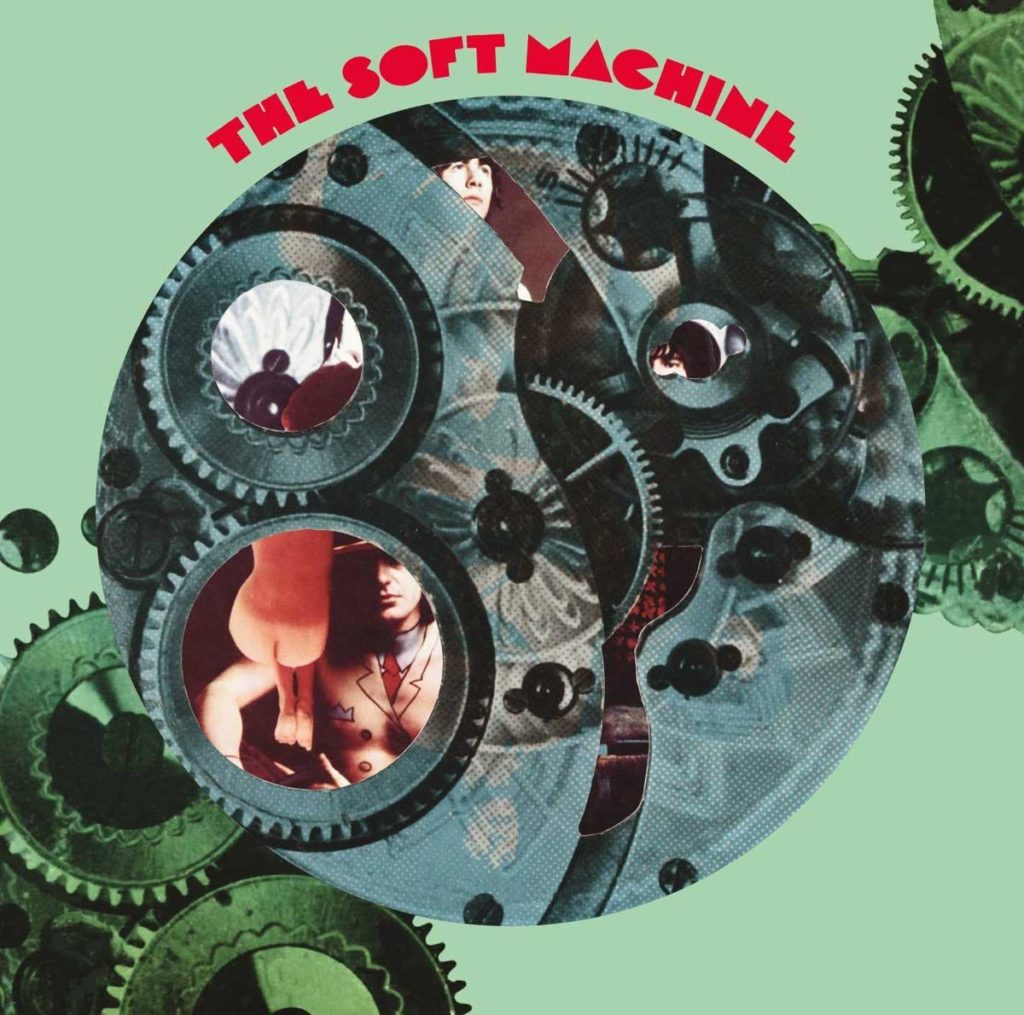

It was short-live though, as Ayers quickly left and Wilde Flowers promptly split into two bands: Caravan (Sinclair) and Soft Machine (Wyatt and Hopper). The initial Soft Machine lineup included both Kevin Ayers and Daevid Allen and was joined by keyboardist Mike Ratledge, whose fuzz-infused organ sound became one of the early psych/prog signatures.

Wyatt provided his very distinct jazz-style drumming, but also initially shared the vocals with Ayers.

Ayers left after Soft Machine’s debut album (1968), considered to be one of the most influential of the period, leaving Wyatt as the sole vocalist in the band.

Soft Machine Turns into a Machine Molle

It was possible that Wyatt’s vocals were what made the sound of Soft Machine so special. But it was also equally possible that those vocals, and Wyatt’s outlook on music and what it should express in general, were what started driving the wedge between himself and the rest of the band.

Ratledge, Hopper, and saxophonist Elton Dean who joined the band along the way, were proponents of complex instrumental music, really serious stuff. Wyatt on the other hand always thought that complexity is not the sole element that makes music sound good. He never shied away from danceability, and his lyrics were laced with hefty doses of humor, even sarcasm. He was also one of the initiators of including nursery rhymes, even nonsensical lyrics, that became quite a favorite among British bands of the time.

He never shied away from danceability, and his lyrics were laced with hefty doses of humor

The rift within the band grew, and by the third and fourth album, his participation in the band’s sound became more and more minimal with Wyatt leaving after Fourth. Actually, Wyatt’s disagreements with the band had another personal undercurrent. He was becoming a true alcoholic, something sped up by his friendship with Keith Moon, the late drummer of The Who, whose alcoholism is one of the most recorded in rock history.

After leaving the band, Wyatt participated in a number of prog-oriented projects like Centipede and recorded his first solo outing, The End of An Ear. It was a specifically eccentric release, comprised mostly of Wyatt’s vocals and tape effects. Wyatt then decided to form his own band, Matching Mole. In Wyatt’s typical sardonic manner, the name of the band was a sound play on the French version of Soft Machine, machine molle. The two albums the band recorded were a double product. On one side they were typical of the instrumental prog leanings of the time. On the other, Wyatt started expressing his left-oriented political views more and more.

A Serious Accident that Saved a Life

After the two Matching Mole albums, the band started falling apart and Wyatt began preparing material for his second solo album. But at the beginning of June 1973, he suffered a life-changing accident.

Attending a party, heavily inebriated, he fell through a fourth-floor window. He became paralyzed from the waist down and has been using a wheelchair from then on. According to Wyatt himself, this serious accident and becoming a paraplegic, actually saved his life, as he had to quit drinking forever.

The high esteem Wyatt enjoyed with other British musicians and artistic figures became evident in the aftermath. Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, and legendary radio host John Peel organized two concerts in Wyatt’s honor and raised a substantial sum of money geared towards the recovery of his health. Later on, Wyatt and his wife Alfreda Berge (a lyricist in her own right) were also financially and materially supported by supermodel Jean Shrimpton and actress Julie Christie.

Life drama, on the other hand, pushed Wyatt to rethink his music in general. He had to completely change his drumming style as he couldn’t use his feet anymore, but he started gaining proficiency with other instruments, raising them to a level of excellence.

The changes were already evident of his first post-accident solo album Rock Bottom — obviously a self-jab at newly raised circumstances. Soon after, one of the initial single releases for then fresh on the scene Virgin Records, Wyatt released his version of the Neil Diamond/The Monkees hit “I’m A Believer.” Produced by Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason, the single promptly hit number 29 in the UK chart. However, when Wyatt was to appear on the Top of The Pops TV show, the producer of the show thought that his use of a wheelchair “was not suitable for family viewing”, and wanted him to appear on a normal chair. Wyatt refused and appeared in a wheelchair anyway.

From Guest Appearances to Serious Solo Work

During the ’70s, Wyatt came up with only one album under his name, Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard (1975). Yet another album with a very telling title. An album where Wyatt showed his penchant for free jazz forms and the likes of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. But even there, it was Wyatt’s distinct vocals that lead the way.

Also throughout the decade, Wyatt participated and lent his vocals to a number of projects of other musicians, from Nick Mason’s first solo album to Mike Mantler’s avant-garde jazz project Jazz Composers Orchestra.

Starting in the ’80s, Wyatt started concentrating on creating solo albums that grew in musical diversity, but also in political and social engagement. Standouts are exactly what that name implies, and include albums like Old Rottenhat (1985), Shleep (1997), Cuckooland (2003), and Comicopera (2007). Throughout, Wyatt always featured his brilliant penchant for covers, including Elvis Costello’s “Shipbuilding” (actually written specifically for Wyatt to interpret) and Nile Rogers’ “At Last I Am Free.”

And it’s Always that Voice…

With all his musical knowledge and intelligence, personal literacy, and social engagement, it is still Robert Wyatt’s voice that stands out with some unknown, enchanting properties.

Probably the best description of Wyatt’s vocals came from poet and translator Michael Hofmann in his article on Wyatt in The Baffler:

“It seems odd to me that a band with the endlessly mellifluous bass-baritone crooner Kevin Ayers should have had someone else do the singing (and Ayers wrote most of the songs as well). But Wyatt both held down the drums and sang. His voice—like nothing and no one else, incapable of disguise, anyone who’s heard it instantly knows it, but how to describe it?—not falsetto but high, fragile, reedy, cracking. A yearning, aching, keening sound. Not trained, and probably not much amplitude. In the German, “eine Kopfstimme,” a “head-voice,” not from the body. Moving in its weakness, not powerful. If a voice can be high and hoarse at the same time, then that. A sort of gruff treble. Often holding a note past its sell-by date. Perhaps the oft-noted underwater aura of Wyatt comes from that. Not just shipbuilding, but also breath-holding. Also, an unfeignedly English voice with its banal, corrupted English vowels.”

Robert Wyatt may have retired from making new music, but the legacy he left behind is as strong as any.