Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) drew rave reviews at the Sundance Film Festival, as it assembled first-rate concert film from footage that had been buried for nearly five decades.

The film featured concert footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival, which was held in Harlem over a series of weekends in 1969, with the featured acts including the likes of Sly and the Family Stone, Gladys Knight and the Pips, The 5th Dimension, and a very young Stevie Wonder.

The festival took place the same summer as Woodstock, and while the latter festival was filmed as part of a documentary and soon became part of the boomer firmament, the film of the Harlem Cultural Festival was never sold to any broadcaster. The footage then spent several decades in a basement.

The film featured concert footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival, which was held in Harlem over a series of weekends in 1969

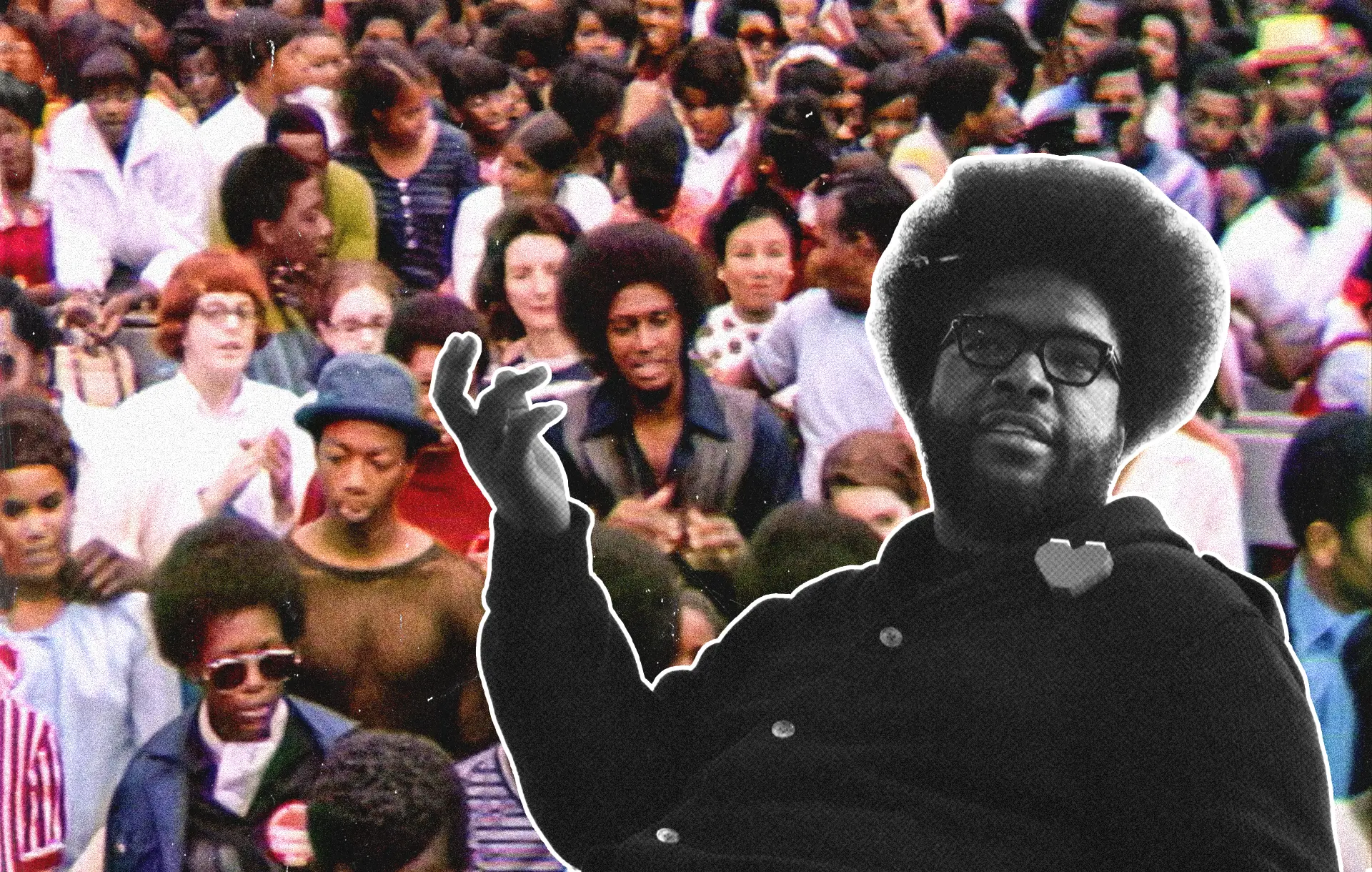

Summer of Soul, the resulting documentary, represents the directorial debut of Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, The Roots drummer, band leader, and producer. The film, fresh off those accolades, debuts both in theaters and on Hulu July 2.

Earlier this month, we joined Questlove for a virtual press conference in which he discussed the film, its music, and what he sought to accomplish with his first film as director.

First, he discussed how he first became aware of the footage that became Summer of Soul.

“I first, inadvertently, saw the footage back when The Roots first went to Tokyo in 1997, and my translator for that tour, who knew that I was a soul fan, took me to a place called the Soul Train Cafe,” he said. “Unbeknownst to me, I was watching two minutes of Sly and the Family Stone’s performance.”

“But because it was of what I knew to be Camera 2, or the bird’s eye view, of the nosebleed section, I didn’t know I was watching the Harlem Cultural Festival. I just assumed that all festivals in the ’60s were from Europe because America didn’t really have that culture yet ― only to find out, exactly 20 years later, when David Dinerstein and Robert Fyvolent told me that they had this footage, and they wanted me to direct the film.”

“So, first seeing it without knowing it in ’97, and then presented to me in 2017, and even then I didn’t believe it was real.”

The director also discussed how the project challenged him as an artist.

“Without being all touchy-feely with it, this project more than anything has helped me develop as a human being,” he said. “I will not hesitate to admit, that of all the things that I’ve done creatively, this is the one I was really really nervous about, and by nervous I mean scared. Partly because I’m a perfectionist. And what I will say is this film has really brought out an awareness and a confidence in me, that I never knew I ever heard.”

Without being all touchy-feely with it, this project more than anything has helped me develop as a human being,

“A lot of times, everything I do creatively is behind a shield, behind a drum set, behind my dad, behind Black Thought, behind Jimmy, behind turntables,” Questlove added. “With the exception of teaching at NYU, you guys have never experienced me, one-on-one… there’s always a barrier that keeps you from getting there, and that’s how I thought I liked it.”

“But I will say, the amount of confidence I got as a human being, [the movie] was a game changer for me.”

He also discussed what he learned about “the power of editing.” The original cut he put together of the film, he added, was over three hours.

Questlove was also asked about the focus on gospel and soul music in parts of the film.

“One thing I’ve always noticed, when I play really intense soul music for younger people, they tend to find James Brown yelling, like humorous. That’s funny to them because we live in a meme/gif culture,” he said.

“So, those three seconds of something out of context can seem funny to people. There was a lot of I guess what we can call primal musical expression, or primitive/exotic expression, in layman’s terms: people acting wild. And I wanted people to know that that was more of a therapeutic thing than anything.”

“I wanted to people to know that this just isn’t Black people acting wild and crazy, that this was a therapeutic thing. And for a lot of us, gospel music was the channel, because we didn’t know about dysfunctional families and therapy like we have now.”

He was conscious of what this meant for him as a director ― starting with what he wants in an ending and working his way from there, just as he’s often done with Roots shows.

“I wanted to make my entry in the film world,” he said. “My version of inserting myself in this film… was Stevie Wonder’s drum solo. I figured that was the best way for me to crash land, into your lives, as a director, without really it being about me. We have not seen Stevie Wonder, sort of in this light of a drummer, so I thought that was the perfect beginning. So that’s pretty much how I crafted the show.”

I wanted to people to know that this just isn’t Black people acting wild and crazy, that this was a therapeutic thing

The film bears the unique directorial credit “A Questlove Jawn,” which is a bit of local slang from the director’s hometown of Philadelphia, similar to the way Spike Lee calls his movies “A Spike Lee Joint.” We asked Questlove, who wore a shirt emblazoned with that phrase during the press conference, whether he had to fight to use that credit.

“I had to register that with the [Director’s Guild of America], and they approved it. Actually, that was my production partner, Joseph Patel, it was his suggestion. I was really trying not to insert myself in the film. In the very beginning, I was showing drafts to people, a lot of the complaints I got were ‘wait- you’re not in this, we need to hear your voice.'”

“And so I begrudgingly put my voice at the very beginning of the film, asking the first question. And that candid moment I had with Musa Jackson at the end… I was really careful not to insert myself in the story because I wanted this to stand on its own.”

“At the very last minute, I let ‘A Questlove Jawn’ through.'”

When asked who on the show he’d most like to have played with, Questlove said the “Captain Obvious answer is Stevie Wonder,” although he also referenced B.B. King, whose set was “on fire.”

He also said that the editing process began in early 2020, just before the pandemic got underway.

“I will say that there was a point where I was wondering, ‘could I take the same approach that I take to DJing, or putting a show together, with this movie?’, and that’s exactly what I did. For starters, for five months I just kept it on a 24-hour loop, no matter where I was,” he said. “And if anything gave me goosebumps, then I took note of it. And I thought if there were at least 30 things that gave me goosebumps, we could have a foundation.”

It was also important to Questlove to look at the Black side of the 1960s counterculture, especially with the performances of Sly and the Family Stone.

“Oftentimes, when you think of counterculture, you think of hippies and white people and whatnot. I wanted to sort of investigate the Black side of things.”

The director also described how he got the audio to work with the footage.

“The million-dollar question ― there are two million-dollar questions with this film that are still unanswered. One, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t find any direct connection to [Harlem Film Festival promoter] Tony Lawrence ― I don’t know if he’s alive or dead, I don’t know where he lives ― nothing of his legacy…”

“The other thing was, how could that audio be so pristine? The audio that you hear in the movie ― this is not to discredit our wonderful sound team… we had to do maybe a 2 percent adjustment on the audio. The audio that you hear with the music is the dry rough mix ― the soundboard, the reference mix. For the life of me, I can’t figure out how 12 microphones were utilized in a way so powerful.”

Maybe this film can be, sort of a sea change for these stories to finally get out.

A positive side effect of the film is that Questlove has been hearing from others about music moments from the past that also remain unseen and could potentially resurface.

“This isn’t the only story out there… in the last three to four weeks I’ve gotten DMs from professors at universities letting me know that [so and so] shot concert footage for 20 hours, for something that they did… so this isn’t the only footage that’s just laying around unscathed. There are 6 to 7 others,” he said. “So maybe this film can be, sort of a sea change for these stories to finally get out.”

“This is not my last rodeo with telling our stories,” Questlove said. “If anything I’m more obsessed more than ever in making sure that history is correct so we don’t forget who this artist is, or what that event is.”