“288—that’s the California penal code for lewd and malicious conduct with a minor. The film is about sexual abuse of a child, so what do you call a film like that? Having fun with uncle?” Jack let out a sardonic laugh. “So I just called it 288.”

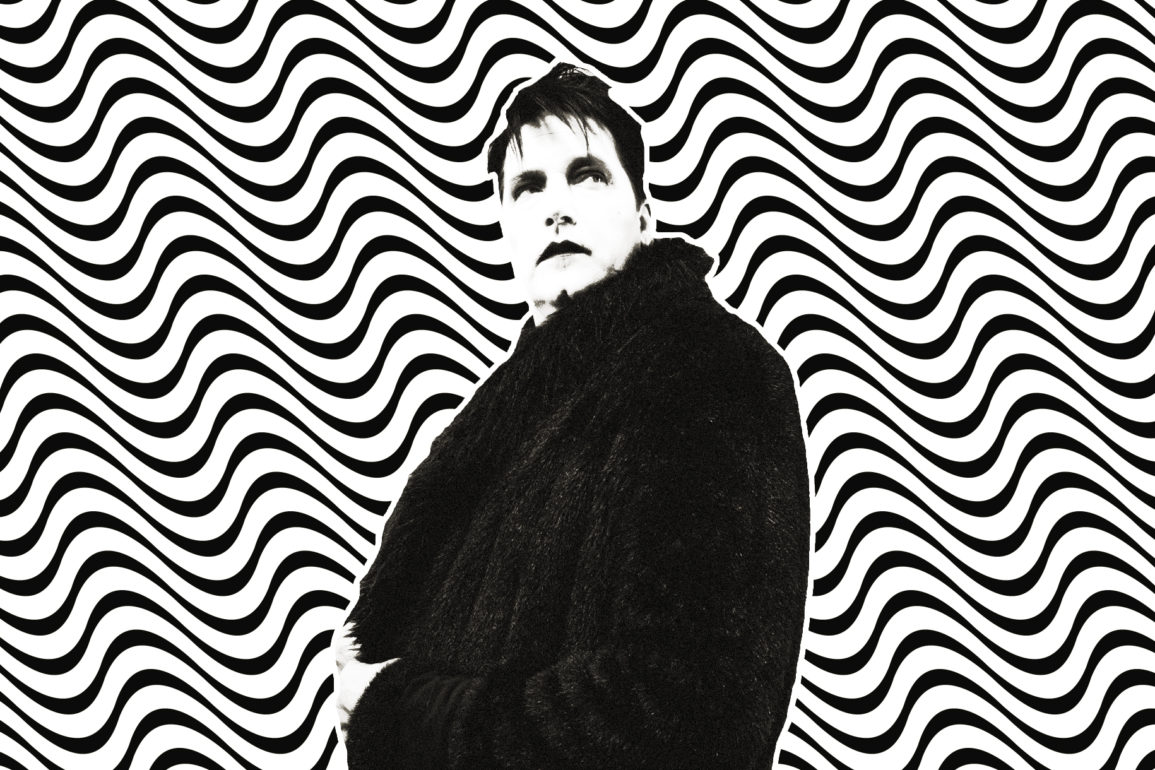

I was talking with Jack Grisham—lead singer of the pioneering punk rock band T.S.O.L—about his new (and first) short film 288.

Launched in 1978, T.S.O.L. helped to bring vociferous political messaging to the forefront of the punk scene, wailing direct social critique over charging rhythms and treble-rich guitars. With the release of the band’s first full length album—1981’s Dance With Me—T.S.O.L. took a turn into darker, more gothic themes, most notably with the track “Code Blue,” a celebration of necrophilia that my first band used to cover back when I was a kid, much to the horror of our parents. In 1983, T.S.O.L. gained even more distinction when a live performance of the band featured in director Penelope Spheeris’ Suburbia—an uber-gritty look at the early ’80s punk culture which (completely unrelated to any of this) also boasted an appearance by a young, pre-Chili Peppers Flea.

T.S.O.L. went on to go through a variety of iterations and lineup changes—including a confusing early ’90s period during which there were two different versions of the group performing under the same name. In 1999 Grisham and the original lineup finally regained sole ownership of the name, and they’ve been performing largely unchanged ever since. Over the years Grisham has worked on a slew of outside projects, including fronting the band Joykiller, writing a number of books, and now directing his first short film, 288.

It’s a disturbing, impactful twenty-minute viewing that portrays several middle-aged men talking about their experiences as survivors of sexual abuse, as well as an older man who asserts that he feels no guilt for his role as an abuser. It’s a difficult watch—so realistic that I didn’t recognize it as staged rather than documentary until I spoke with its director.

“So I didn’t tell the actors what the movie was about,” Jack revealed. “I didn’t tell the cinematographer what the film was about. No one knew what it was about. I handpicked these guys and I told them, ‘Talk to me about loss, talk to me about frustration. Have you ever been hurt? Has a friend ever cut you from behind or stabbed you in the back?’ And so they were giving me real answers about different questions. All those answers are honest answers. But they’re not about being sexually assaulted as a child.”

It’s a difficult watch—so realistic that I didn’t recognize it as staged rather than documentary

This novel filmmaking method paid off, because the whole thing feels starkly open and honest, even if it emerged out of fabrication. But as it turned out, there was more realism beneath the fiction than even its creator knew.

As the actors answered Grisham’s questions, they gradually realized what the film was actually about. And that’s when something unexpected occurred.

“As the movie [filming] went along, Glenn, who plays the abuser, and myself—we were the only two guys who admitted to being sexually abused, right?” Jack explained. “But then their answers started clicking buttons with them and opening up these areas where they started recalling sexual abuse. I actually ended up having a couple actors bail on me saying they can’t be part of this—‘This is really fucking with my head.’ So it started with Glenn and I being the only two people who admitted to sexual abuse, then as the movie kept going and the interviews kept going, some of the other guys in the film came out and said, ‘Hey, I was also abused. I was also sexually abused.’ It was really fucking random. It was really like a weird almost-therapy session. So much so that Scotty, one of the actors in the film actually contacted the police to turn in the guy that sexually molested him, and it turned out that he was in prison already serving time for another molestation charge.”

It should come as no surprise that genuine abuse bubbled to the surface. While studies show that 1 in 6 boys will be sexually abused, less than 10% of these crimes are ever reported. As a result, it is tragically common for these boys to grow into men who survive in silence.

The most significant and disturbing role in 288 is billed as the Perpetrator of Abuse. Played by Glenn Davis, this sneering, contemptuous portrayal comes off as all-too-real as he repeatedly asserts that there is nothing wrong with abusing a child, and that it is in fact the victim’s fault. As mentioned previously, I thought it was real, and later wondered how the actor delivered such an authentic performance.

“The whole thing was really trippy,” Grisham said. “So with the Abuser—with Glenn—all those things had been said to him. I would feed him some lines and say, ‘Go off on kids that think they’re entitled. Go off on kids who think they’ve got something coming.’ So he would go off on that and then he realized as it progressed what he was, and really started channeling the guy who had abused him.”

This trend of art imitating life continued.

There’s not a lot of guys from music—at least not the kind of music I’m in—who are willing to talk about this kind of shit

“The editor was just in the process of dealing with his mother who had been physically and emotionally abusive to him since he was a young boy. She has Alzheimer’s and is sick now, so he was dealing with a lot of emotions like Fuck her, but at the same time, But she’s my mom. Basically there was not anyone in that film that had not been touched by abuse.”

Later what Grisham referred to as a weird almost-therapy session was brought into an actual therapy space.

“One of the guys, Jeff, who was in the film, he’s a counselor at a high-end, rehab-in-the-desert thing. He actually used this film the other day in a presentation to get people to open up and talk about their trauma.”

“You really don’t realize how prevalent it is. Especially in the circles I run in—the recovery circles. I’ve been sober for 31 years. So many of the people in those rooms had been physically and sexually abused.”

I asked Jack whether his music had been therapeutic in any way. His response was unequivocal.

“No. None of it. Not until I got…None of it really started…”

He drifted off, considered, then continued.

“When I was a little kid they were sending me to counselors trying to figure out what was fucking wrong. You know? Like why is this fucking kid shitting his pants when he’s 11 years old? Why’s he lighting fires and going missing and fucking hurting animals? What is happening here? So they had sent me to therapy but there was a whole lot of shut off nothing.”

“But once I got sober all this stuff started coming out, and it was a real bummer. I couldn’t hug or be hugged by somebody. I first realized how hard it was to be touched by someone. Like, I could fuck anything—but don’t show me love! I couldn’t stand it. It was painful. It was literally like throwing holy water on a demon. It fucking burned.”

“So I would go through things where I forced myself to hug people. Like with my niece who was almost 21 years old, the first time I ever hugged her it was by accident. We were at a night club and she had a fake ID and I was getting used to hugging people. And I saw my niece and I hugged her, and it was such a huge deal to her that she actually went to a payphone and called her mom and said, ‘You won’t believe this but your brother just hugged me.’ So it took a lot to break a lot of those fucking barriers.”

“One of the things I was most worried about was that I would end up hurting my children. Thankfully because of recovery and therapy my little girls have never had to suffer that from me. In any way.”

Now with the release of 288, Grisham is taking his therapy public. It’s not the first time he’s opened up about his troubled history—his 2015 memoir A Principle of Recovery took a deep dive into the tribulations of getting sober—but it is the first time he’s put it to film and made it a communal experience.

“It was a letter to the abuser saying, ‘Hey man, do you ever think of me? Do you ever recall when you touched me?’ There’s not a lot of guys from music—at least not the kind of music I’m in—who are willing to talk about this kind of shit.”

I asked if he plans on making more movies.

“Yeah! I’m actually working on directing a documentary for my band—for T.S.O.L. It’s the 40th year anniversary of our first two records, so I’m doing a documentary about the inception and the growth of that band. Everything’s on hold except for this movie right now.”

By everything he means performing with the band, which—like pretty much everything else—is largely on hiatus until the pandemic dies down. So how is he handling the situation?

“I feel bad for the people that have died and for the people that are having trouble, but for me it’s like—I write. So isolating is not an issue. I kind of enjoy it. I live looking at the ocean, so I get up and sit out on my balcony and I watch the ocean and then I write. So I’m alone all the time anyway. I keep doing stuff and turning more stuff out. It hasn’t slowed my output any.”

As for his work with the band…

“I just finished a song that was all done remote. Everybody was in a different area. We’ve been doing a couple of covers. We covered “Sweet Transvestite” from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And with some other friends we just finished doing a cover of David Bowie’s “Can You Hear Me” off Young Americans. That was really fun because everybody was somewhere else, so we were just mailing tracks back and forth.”

I never had a punk rocker back then write me a letter saying that I was a leftie, communist piece of shit

While on the subject of music, I asked how the punk rock scene—which Grisham and his band had helped to create way back in the early days of the Reagan presidency—has changed over the years.

“Let me tell you something—I never had a punk rocker back then write me a letter saying that I was a leftie, communist piece of shit for hating Reagan. And that’s the bottom line. And that’s the difference between then and now. It’s fucking crazy.”

He was referring to a conservative, alt-right presence that has become increasingly (and bizarrely) vocal among punk rockers. This crowd has a tendency to spew its bootlicking ire toward Grisham via the T.S.O.L. Facebook page, which he moderates.

I myself have seen some of these comments. They assert—astoundingly—that punk rock isn’t supposed to be about politics, which always makes me wonder: Why are they following a band that wrote songs with blatantly political messages like “Abolish Government” and “World War III”? What do these conservative punkers think of the track “Superficial Love,” which closes with Grisham shouting “President Reagan can shove it”?

“I don’t think they understand at all,” Grisham said ruefully. “I just don’t get it.”