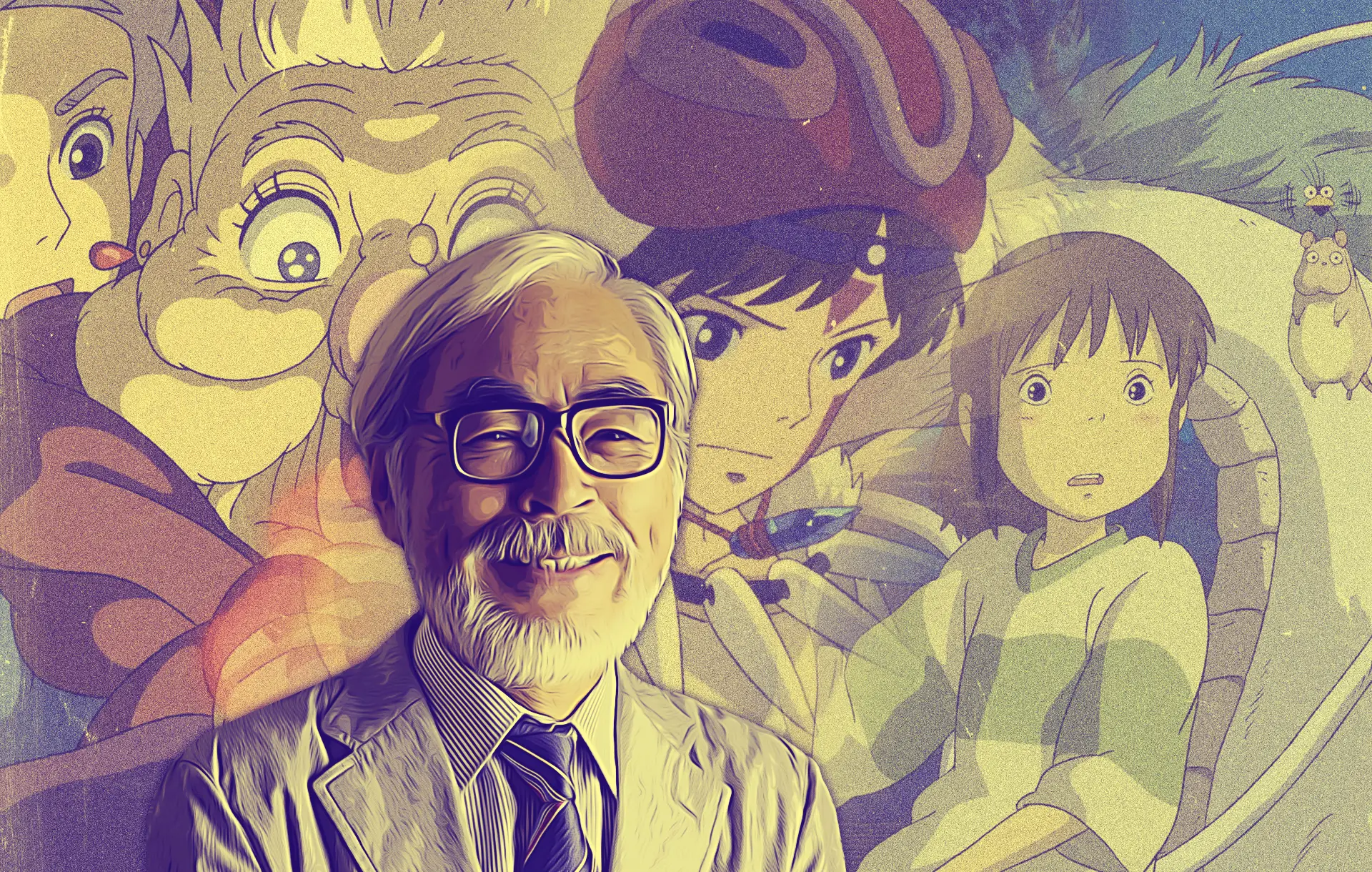

Many artists possess creative faculties that seem superhuman. Among them are those able to harness their creative force of will and impress it on the world through their medium of choice, becoming iconic in their form of expression. I talk of people like Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary animator whose style and direction are high examples of what is possible in art. His movies embrace the fantastical but also transmute it, adding his own tincture of quirkiness and absurdism by bending concepts in a way that Lewis Carrol might have envied. The worlds of Miyazaki are many: there’re chaotic, post-apocalyptic realities ravaged by giant mutant insects; they’re tribal-feudal lands where warriors fight mythical beasts and ‘proto-industrialists’ armed with early medieval weapons; and they’re fantasies involving children encountering hidden worlds and forest spirits.

An Animated Cornucopia of Delights

For over 40 years, Miyazaki has released an impressive range of films that explore different genres, delving into sci-fi, fantasy, magical realism, and even supernatural realms. His stories play on our curiosities with a host of incredible concepts such as reclusive wizards, squired ‘witches-for-hire’, forest spirits, sentient fires, floating castles and ‘worlds that exist beyond the everyday physical world.’ Throughout all these films, recurrent themes often thread cohesively through many storylines, including strong female characters on challenge quests to prove themselves, coming of age tales, magical curses that may or may not be broken, the destruction of the natural world, and a free-spirited sense of wonder symbolized through love, hope, and youthful innocence.

His movies embrace the fantastical but also transmute it, adding his own tincture of quirkiness and absurdism

Some of the greatest animations Hayao has directed or been otherwise creatively involved with include Castle in the Sky, Nausicaä of the Valley Wind, My Neighbour Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Ponyo, Whisper of the Heart & The Secret World of Arrietty (both of which he wrote screenplays for) as well as his major classics: Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and Howl’s Moving Castle.

Deep Diving the Classics

Spirited Away

After the turn of the millennium Miyazaki’s films exploded into the wider mainstream with the release of Spirited Away. The film opens on a young family travelling to their new home in rural Japan. However, they soon become lost on some leaf-strewn backroads and eventually stumble across a grand stone entrance of an old amusement park. Forest trees and old stone shrines decorate the path and the parents decide to get out of their car to explore it – despite the reluctance of their daughter. Here is where all normality is abandoned. In a blending of the absurd and the real, the stone entrance seems to act as a gateway, or portal, to another realm where spirits thrive.

The little girl, Chihiro, soon finds herself alone as her parents succumb to a frightening curse that turns them into animals. In this way, by removing her guardians from the picture, Miyazaki forces his main character on a challenge quest to free herself and her family. From one moment to another, this shy and stubborn girl is suddenly plunged into a strange world where she must learn to fend for herself. Pitted against strange creatures and travelling spirits, young Chihiro must find a way to survive. To do this, she takes on a job at a traditional bathhouse run by a powerful, malevolent witch called Yubaba. This idea, that a young girl must take on the responsibilities of grown ups, is not a new one. In fact its a very old idea that has existed for centuries where older girls were tasked with bringing up their younger siblings and help with the running of the household. So when you consider that element of social history, Chihiro entering the workforce to ‘get by’ symbolizes that loss of innocence that comes with entering and navigating the adult world.

There is an allusion to exploring one’s own identity or finding oneself

This theme of coming of age and or ‘the gaining of wisdom and maturity’ is again mirrored in one of the witch’s servants, a young boy named Haku. As the narrative unfolds we learn that he forgot his real name and Yubaba keeps him trapped in servitude until he can recall it or someone reveals it to him. There is an allusion to exploring one’s own identity or finding oneself when one is lost. Yet in a way, it also lends to the pain of growing into people that society and adults want them to be, rather than what they would choose to become, thus losing their own identity and child-like ways.

Princess Mononoke

Miyazaki’s epic hit of the late ’90s is a visually impressive action-drama set in the Muromachi time period, where supernatural beasts are at war with humans. In its classic opening battle scene, Ashitaka, a young warrior and prince of the Emishi village-clan, faces off against a giant god-spirit in the form of a boar. The beast is felled by arrows and dies suffering a painful, demon-mark curse, but not before passing the curse on to him. In a definitive moment, Ashitaka acquires the thing that drove it to madness: a great, twisted ball of iron shot. Here we have two themes – dramatically presented in tandem – that have relevant ties to the real world. Firstly, humankind is constantly at loggerheads with nature; and secondly, the age of industry and the technology that comes with it has allowed the creation of weapons and metal balls of gunshot which are ultimately devastating the world and the natural order of things. In other words, humans go about destroying the world for the sake of progress and, by doing so, break their deeper connections to it.

Our civilized descent into the human domination of the world where we have sacrificed our spiritual links

Ashitaka soon finds his accursed arm has acquired great strength when using his bow, but this comes at a terrible price: the mark begins to spread and the grim sentence of death is all but assured. Because of this, he must cut ties with his village and leave forever. It doesn’t take him long to run into a group of destructive ‘proto-industrialists’ from Iron Town, led by Lady Eboshi, who fight off their enemies with matchlock guns and hand cannons. These enemies take the form of a white wolf and a wild girl called ‘San’, the adopted human daughter of Moro, an giant wolf-God. In this clash between gods and humans we see one of Miyazaki’s strongest beliefs: that modern civilization is ravaging the natural beauty of the land, plundering it for resources. Its a social-political commentary on our unsustainable way of living, yet he also uses this concept to delve deeper, comparing the level of destruction to an evil act committed on the living earth. This is something that is epitomized by Lady Eboshi, who aspires to rid the world of the dear-like forest spirit, aka the Night Walker: the god that presides over life and death in Cedar Forest. She believes that by cutting off its head and killing it, she will rid the forest and the lands of the spirit’s influence, allowing her to lay claim to all its natural spoils. In this, we could be called to pause and reflect on the state of our environment and the destruction of ancient forests, the irrevocable loss and extinction of countless unique animal species, and the developing climate crisis. In addition to that, the killing of the Night Walker is a very veiled allusion to our civilized descent into the human domination of the world where we have sacrificed our spiritual links to the land to feed our hunger for advancement.

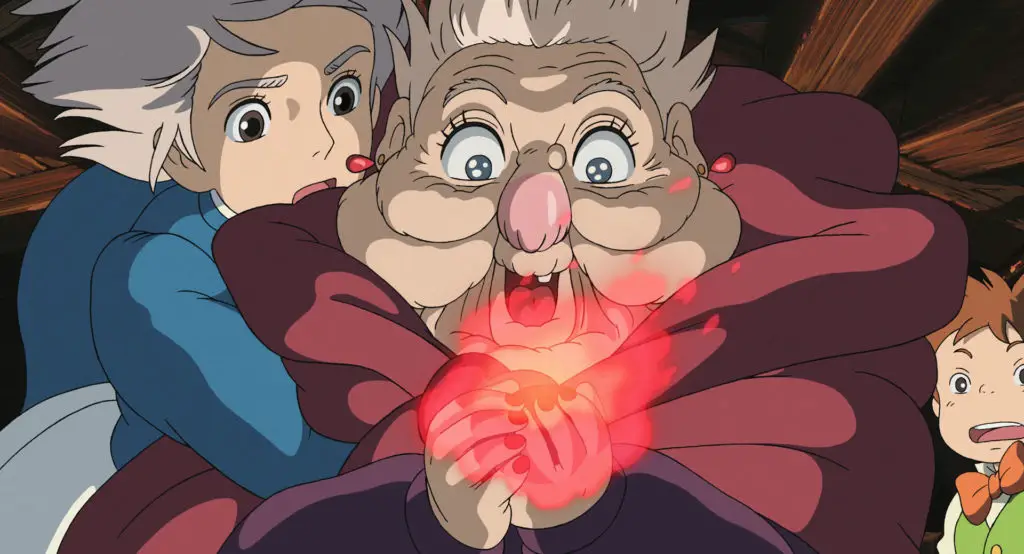

Howl’s Moving Castle

Howl’s Moving Castle is easily one of Miyazaki’s best films and is one of the directors favorite films. This 2004 adaption of the book by Diana Wynne Jones is considered by many to be a hallmark of the spellbinding Miyazaki-Studio Ghibli style. The story centers on a young milliner called Sophie who is rescued from danger by the dashing wizard, Howl. However, what starts as a spellbinding encounter quickly takes a mortifying turn when the Witch of the Waste, spurred by jealousy of the wizard’s charming of Sophie, casts a spell on the girl, preternaturally aging her. The transmorgification of Sophie is a curious plot device that artfully explores two sides to her personality simultaneously: the cautious, quiet, sensible girl who dutifully runs her mother’s shop and her transformation into an older, adventurous woman. However, it also shifts the focus from films fixated on the trope of young hero journeys to one exploring the notion of characters of advanced age still having adventure in them. As Sophie sets off on her own journey, one can clearly see a positive take on aging: far from her age being a curse of time, Old Sophie exhibits resourcefulness, cunning, and even a motherly gentleness.

One can clearly see a positive take on aging: far from her age being a curse of time

Unlike other popular fantasies like The Beauty and the Beast where the beast returns to his original form, this story takes an unusual approach, negating a tidy fictional ending by never resolving Sophie’s curse. The spell is never completely broken and although she returns to her correct age, her once chestnut hair is now silver. Throughout the film we sometimes see her briefly return to normal before reverting back to the older version of herself. And this in itself is fascinating as on one occasion, Sophie talks passionately about Howl, and during her speech, her voice and features become younger. Somehow her love of Howl, as in traditional fairytales where love lifts curses, made the change possible. Yet, it is not just the romantic love of two star-crossed lovers, but a love of the true person that resides within (facades like age and appearance aside) and loving innocently with a child’s heart; which is true for Howl in a literal sense, who, by some old magic, retains the heart of a boy despite his adulthood.

High Art Animation: Not Anime

People who don’t go for anime or prefer other stylized animations are still aware of its influence. Outside the devoted fanbases, anime has always been on the periphery in some form or another. Shows like Dragon Ball Z captivated Saturday morning cartoon watchers and whole generations sang “Gotta catch ‘em all!” in one of Japan’s largest exports: Pokémon – which has become a mega-media franchise and merchandising phenomenon that has spawned TV shows, games, a Pokémon Go augmented app, and of course, the legendary playing cards that kids still play today.

Other shows less known to non-watchers of the medium, but still floating at the edges of those with eclectic tastes that mesh with awesome oddities, are things like Ghost in the Shell, Fullmetal Alchemist, Akira, and, to a lesser extent, the avant-garde cult classic, Aeon Flux. Yet, it would surprise many to learn that Miyazaki himself doesn’t describe his own work as anime. In the past he has downplayed and distanced himself from the medium that brought him mainstream success due to the abundance of low quality productions that came out of Japan’s ’80s economic boom which, to him, often traded themes of ‘love’ and ‘departing for new horizons’ for shallow commercial gains.

When you learn how strongly he feels the disillusionment of the anime-obsessed ‘otaku’ geek subcultures and their modern creators, it helps to understand his creative mind. As an animator, writer and director, Hayao Miyazaki has always been intent on pursuing deep stories with strong messages which are driven by living characters that inhabit beautiful landscapes – represented in the famous, high-detailed artistic development of his creative team’s productions. With this in mind, Miyazaki’s most enduring magical films become curious coded fantasies that reveal universal truths through powerful, thematic stories.