During these enervating hours of isolation, where uncertainty toward the future seems to be the unwanted companion of us all, we are called to make ethical choices to protect our own and other people’s safety and health. In this regard, major crises have always turned out to be the most significant opportunities to grow by practicing the fundamental values of a united country, regardless of race, political faith, religion, and culture.

Amidst the initiatives being conducted to boost morale, arts and culture are definitively what’s needed at the end of such historical periods. Rediscovering who we were and who we have become through arts is crucial to a specific culture in order to let people know that they are still important. Whether it’s war or a pandemic that make many of us faceless and nameless victims, the artist is called to intervene in order to restore strength and identity in the society.

Neorealism took place in a very dark time for Italy, and yet it was a sign of cultural change and social advancement.

It’s precisely in this cultural context that Italian neorealism was born. This national film movement, also known as the Golden Age of Italian Cinema, is universally renowned as it delivered a strong response to economic and political malaise in the wake of World War II and Benito Mussolini’s downfall. Neorealism took place in a very dark time for Italy, and yet it was a sign of cultural change and social advancement. Its films presented contemporary stories that were often shot in the same streets that the war had damaged, frequently using non-professional actors.

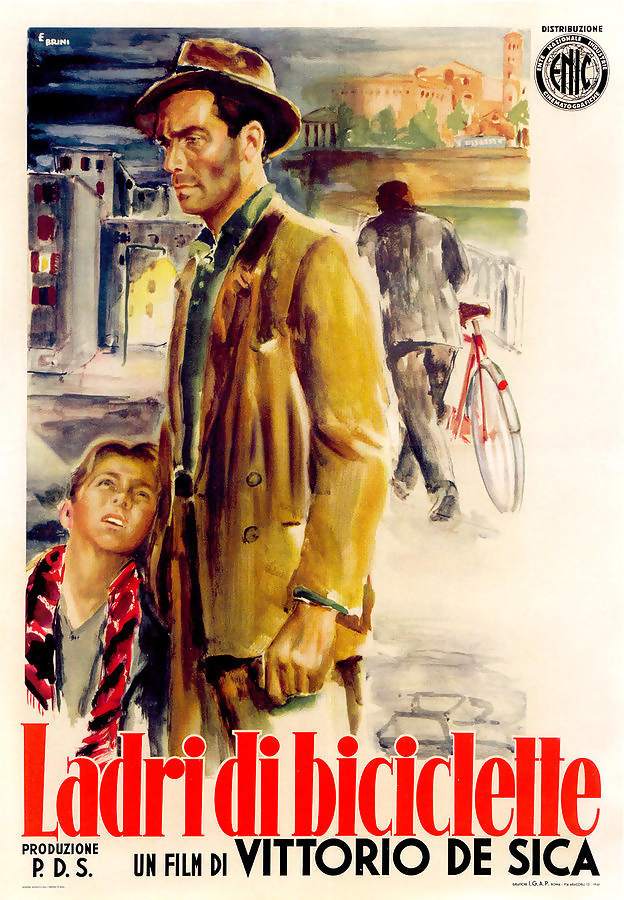

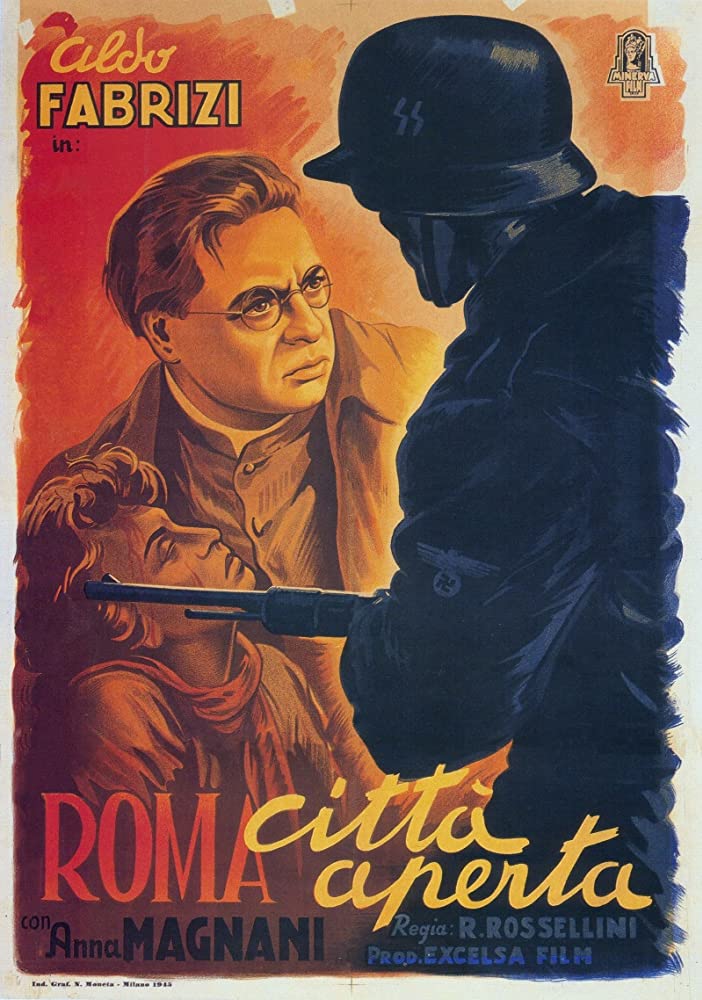

Developed and shaped by the work of great directors such as Roberto Rossellini (Rome Open City) and Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thieves), this movement also constituted an important influence for the work of classic and contemporary American filmmakers, such as Abraham Polonsky (Force of Evil), Martin Scorsese (Mean Streets), and more recently, the Safdie brothers (Good Time).

American Neorealism As a Consequence of Italy’s Past

The themes addressed in Hollywood in the wake of WWII served a similar purpose to the Italian neorealism. However, they had to confront a completely different scenario, which specifically referred to the communists as a threat within the borders of the country. That’s the reason behind the blacklist, whose sole function was to cut off a potential propaganda for communist sympathizers through films and television.

Italian neorealism’s influence on the American film industry has been significant regardless. Only the definition of American neorealism hasn’t found most critics in agreement, especially in consideration of what’s been said above about the risks of being blacklisted in Hollywood. There were a few cases in which young American filmmakers were able, for a reason or another, to embrace neorealist norms and make some unique films in contrast to the studio system. In any case, though, they couldn’t openly declare their purposes.

Amongst these neorealist-inspired works, it’s interesting to notice how this movement took shape in America, specifically through the political and noir genres. Some remarkable instances, which deserve to be taken as frames of references for these genres are Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (1947), Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil (1948) and Jules Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway (1949). Later on, John Cassavetes’ movies showed a different approach, with a much deeper insight on this movement: Cassavetes’ movies offered a better opportunity for audiences to meditate and weigh nihilism as a consequence of a capitalist society, but he did so with such mastery and tact that nobody realized it.

The flawed and tormented characters of the Safdie brothers mirrored the same silent complexity that can be traced in Cassavetes’ characters. They are the most contemporary filmmakers related to this movement, and the proof of this contiguity can be found by taking a closer look at their Top 10 List on the Criterion Collection’s website, where they both chose Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) as their favorite film and major source of inspiration. “This is the holy grail, the ultimate filmmaking bible. It maximizes its use of father/son dynamics and trying, real locations, all while its pure emotional current is completely understated yet very felt. This is one of those before and after films,” Josh Safdie said.

A Neo-Neo Realism: What’s Needed to Boost Morale After The Pandemic

Speaking of before and after films, as Josh Safdie did, there’s a question that seems to come to mind almost automatically after all this rumination about post-crisis artistic movements: what kind of films are we going to watch after this pandemic is over? Such questions were asked during the Great Depression, the Cold War, and after 9/11 in order to find a cure to anxiety and confusion among Americans. After the September 11 attacks, for instance, the unanimous response among studio executives was that, in the wake of such unthinkable horror, Americans needed comedy, fantasy, and heroism – does Marvel ring a bell?

…what if, at least once, we strive to fixate our eyes on the horror that’s happening right now, right in front of us?

To corroborate such theory, we could also take a look at the years of the Great Depression that were crossed by Fred Astaire’s dancing moves and the giggling that followed everything that the Marx Brothers would say. So, as we can see, what we wanted the most, all this time, was to forget our troubles. Whether it’s recession, war, or a pandemic, the kind of movies we apparently need are the ones that offer us a mental diversion from unpleasant events of our lives. In other words, we want to look the other way.

Keeping all this in mind, along with what’s been said about major crises and the fact that they have always turned out to be the most significant opportunities to grow and evolve, I’d like to pose a new question: what if, at least once, we strive to fixate our eyes on the horror that’s happening right now, right in front of us? Perhaps, this would be convenient to acknowledge that in such a confusing and out-of-control reality, a better grasp of said reality might be useful not to let the panic and fear sink in.