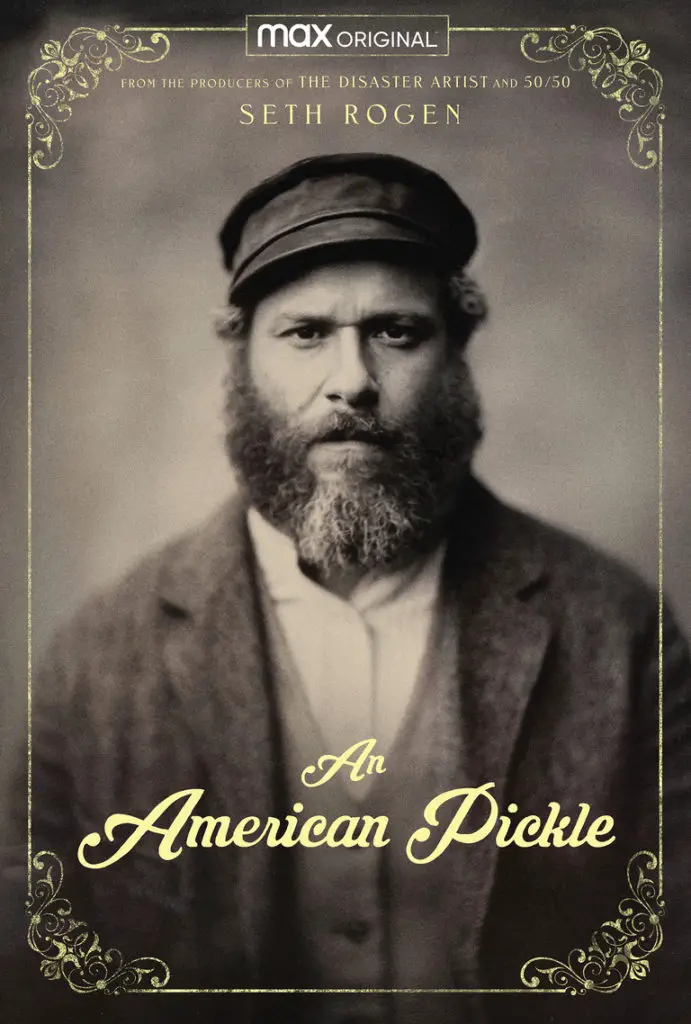

On its surface, Brandon Trost’s An American Pickle is a sweet, breezy film with an oversized heart at its center; its 88-minute runtime makes for a hasty viewing experience, particularly with Simon Rich’s smooth screenplay and John Guleserian’s immersive cinematography. Beneath the film’s surface, however, lies a tale of important history not often taught in America, diaspora, generational detachment from one’s ancestral heritage and trauma, and a unique take on the immigrant story. An American Pickle is essential viewing that enlightens its audience without being too preachy or cloying.

The Pre-Soviet Union Cossacks

In An American Pickle, Herschel Greenbaum’s (Seth Rogen) home is attacked by the Cossacks. When his people are slaughtered, Herschel and his wife, Sarah (Sarah Snook) escape to America. The Cossacks were East Slavic-speaking, Eastern Orthodox Christian ethnic group from the regions of Ukraine and Russia who formed micro-militant communities throughout the former and the latter. Extremely prejudice, they participated in Jewish ethnic cleansing going back several centuries in history.

The Don and Kuban (pre-WWII) Cossacks assisted the White Army in an attempt to violently suppress the communist uprising known as the Bolshevik Revolution and its subsequent ideological and geographical spread, which began the Russian Civil War (1917-1923). The town of “Schlupsk” is a fictional town, but it closely resembles Slupsk, an actual town in northern Poland, closer to the German border than the Ukraine one. In Rich’s New Yorker Novella, Herschel is from the latter. This town largely avoided the conflict of the Russian Civil War, only facing severe persecution under the Nazis in WWII. However, artistic liberties were taken, since the adding of the “ch” in An American Pickle’s fictional city. One can assume this version of Slupsk faced pogroms by the Cossacks during the Russian Civil War.

Regardless of their contributions to the Red Army in fighting the Nazis during the Second World War, prior to the Soviet Union’s rule, Cossacks were largely vile, prejudice, violent, hateful people towards Jews, and Herschel and Sarah’s experiences are a very real, consistent chain of events, leading to ancestral trauma that has gone unrecognized for centuries. When genocide is ignored, it compounds the pain of the victimized peoples.

The Denouement of Diaspora

The Diaspora not only applies to Jews being driven out of Israel, but it also applies to Jews being driven out of places everywhere across the globe in which they’ve settled, where populations are rife with anti-semitism, as well any ethnic population being driven out of a place it calls home.

Diaspora can lead to a loss of one’s certain relationship to their cultural identity. However, despite what Zionists believe, through the passing down of stories, values, and the continued sharing of personal and ancestral history can also preserve one’s cultural identity despite geographical dispersement across the world; Jewish identity, isn’t synonymous with Israeli identity. Judaism, like many religions, also spreads by word and belief. It is culture as well as a religion. These components to a particular people have remained strong wherever Jews have settled. Ironically, however, the most prejudicial pushback from Jewish settlement throughout history has occurred in America, the land of the free.

Many moved to America to face a better life, only to eventually assimilate and lose many of their cultural ties

In An American Pickle, the depiction of Jewish Diaspora is strikingly similar to Armenian Diaspora in America, with both even occurring at the same time period. Both Herschel and many Armenians narrowly escaped pogroms by the Cossacks and Turks, respectively. Both experienced precursors to their genocides more than two decades prior: The Cossacks and the Hamidian Massacres. Many moved to America to face a better life, only to eventually assimilate and lose many of their cultural ties. My family narrowly escaped the Armenian Genocide in the early 20th Century; my paternal grandfather, George Arabian, was born in the port of Vladivostok, Primorskiy, Russia on October 16, 1917, fleeing the Genocide. Eventually settling in San Francisco, his parents died very young, forcing him and his younger sister into foster care.

My paternal great-grandparents fled to Fresno, escaping the Hamidian Massacres in the Ottoman Empire from 1894 to 1896; my great-grandfather, Albert D. Hagopian, and my great-great-grandfather, Peter D. Hagopian, witnessed my great-great-great-grandfather, the village Catholico, beheaded at the behest of Turkish Hamidiye and Kurdish brigands in front of the rest of the villagers because he refused to convert to Islam. George, his sister, Peter, Albert, and I were and are products of the larger Armenian diaspora. And George, his sister, Peter, and Albert faced prejudice and persecution when they immigrated here, and were forced to try and assimilate only be treated as second-class citizens – as “other;” many Armenians were denied property, bank loans, store and restaurant service, etc. Armenians are not white (we are Caucasian – from the Caucasus), but have always been treated as lesser subclasses among white populations, constantly questioned for our place in this society, falsely-labeled, our loyalties questioned, our genocide denied by the country in which we live and its people, who never bothered to attempt to come to terms with Western society’s lack of humanitarian assistance in trying to help reconcile the controversial Armenian Question.

Through the generations, this assimilation caused my family to lose touch with our language, the Armenian Apostolic Church faith, and much of our cultural heritage. However, later in life, I’ve been able to reconnect to much of our heritage, just as Ben did on his forced pilgrimage to Schlupsk, his ancestral home. In that sense, both my great-grandparents, grandparents, and my stories and those of Herschel and Ben’s share further similarities. As do many generations of families that have experienced diaspora.

Later in life, I’ve been able to reconnect to much of our heritage, just as Ben did on his forced pilgrimage

In An American Pickle, the diaspora has multiple effects on mental health, including the consequences of loss of tradition. The way Herschel used to live with death, constantly, in the face of pogroms, ever present in his everyday life, compounded by the religious tradition of preparing for death before it happens and publicly grieving loss as a community, made it easier to deal with. Today, many Americans aren’t equipped with the tools to grieve. It is repressed. It is taboo to overtly grieve, to a certain extent. The importance of physical records being passed down, generationally, especially when genocide has haunted one’s peoples, is an important theme, as Ben keeps Herschel’s family photo album, even adding to it. It was also heirlooms such as these that allowed me to rediscover my ancestral roots as I grew older. My paternal great-grandparents one side and paternal great-great-great-grandparents on the other, and Ben’s great-great-grandparents on both Herschel and Sarah’s sides were massacred by the Turks and Kurds, and Jews, respectively, their records destroyed. Because of this, I, like Ben, don’t even know their names, let alone anything about them.

Mine and Ben’s stories are common entries into the narrative of the long-spanning diaspora experience. Due to such a similar history of oppression and genocide and subsequent diaspora, Jews and Armenians are brothers and sisters. As are all immigrants. An American Pickle is for any viewer whose family originally came to America seeking a better life. For anyone who’s ever felt detached from their familial background. For anyone who’s ever felt removed from their ancestral home, in the figurative and literal term.

A Generational Disconnect

Herschel narrowly escaped the ethnic violence of the Cossacks to work hard and start a family of his own, only to have that ripped away from him. Apart from facing violent persecution (although, Jews face everything from micro-aggressions to overt prejudice today in America), his great-grandson, Ben (also Rogen), virtually shares the same story as Herschel – his parents were taken from him at a young age, and he’s striving to make a name for himself. As a result of generational assimilation, Ben has become less connected to his Jewish identity, and, by not having a family of his own, less concerned with the importance of family as an integral function of society, a rather dated ideology. In fact, he is more concerned with fame and wealth for sake of fame and wealth, two things that would ironically come to the walking-four-leaf-clover Herschel.

Ben’s attitude is a product of American assimilation, which rewards inward, self-obsession, egoism, and materialistic gain over the phony values of the post-war nuclear family. It is also important to note that Ben’s generation marries, and, generally, settles down later in life than Herschel’s generation did – out of many factors, reduction in poverty and persecution largely contributed to this shift in age of marriage and the need to find a mate or mates for life.

Ben is no longer religious. With the imminent threat of his people dying off no longer breathing down his ancestral neck, he doesn’t feel the urgency and responsibility of the necessity of creating a familial empire like the one Herschel refers to – one that would secure that his family, and his people, would flourish for generations to come. He is removed from many of the cultural ingredients that old world Jews would consider essential to their identities; As Ben mentions, being Jewish isn’t what it meant in Herschel’s era. Today in America, for many assimilated peoples, one’s culture, ethnicity, religion, or nationality is an important part of one’s identity, but it isn’t something that necessarily defines a them.

The fight between Herschel and Ben is a metaphor for the generational trauma resurfacing through family dysfunction. Herschel is disappointed that his love for family and culture didn’t extend to Ben, and Ben, in turn, is ashamed that he hasn’t lived up to the glory of his ancestors. Herschel ultimately deems Ben a traitor to his family, and Ben is unwittingly exiled after a wardrobe switch, sending him on a reluctant pilgrimage, which forces him to confront his roots and finally process his grief and his ancestral trauma, ultimately realizing Herschel’s faith isn’t about god, it’s about tradition and community. This switch also forces Herschel to reconcile with the less-flattering qualities of some of his dated views and walk in Ben’s shoes as he pursues an increasingly elusive American Dream.

What is “The Immigrant Story?”

In America, every immigrant story is unique, but virtually all experiences are relatable to others, to a certain extent. An individual or family could be escaping religious, racial, ethnic, cultural, or sexual persecution. They could be escaping poverty in order to pursue the oft-romanticized American Dream. They could be breaking free of an oppressive government. War. Genocide. Diaspora; Life. Liberty. The pursuit of happiness. Regardless of how one or one’s ancestors arrived to America, every immigrant story is relatable in that we, every citizen in America, came here to pursue a better life and secure a safer and more fruitful environment for themselves and their families. That is why it is the immigrant story.

Rarely do things pan out as one ideally hoped for, as the American Dream, and the idea of a free America that emboldens the individual, is as elusive as a four-leaf clover. It was a marketing campaign. An embellished idea that only a minute minority would and will continue to accomplish at the expense of a few.

That is where An American Pickle’s simultaneous earnest and tongue-in-cheek takes on the immigrant story and the American Dream, respectively, stand alone. Herschel brings his old world sensibilities to the postmodern era, infusing it with a motivated, purposeful, goal-oriented work ethic, generosity, and love for family and community, and his infectious behavior and antics can’t help but overshadow his offensively dated qualities, ultimately rubbing off on the world, and, eventually, Ben (after a hilarious run-in with “cancel culture”).

An American Dream

When one adds all of An American Pickle’s ingredients together, they create a complex dish that maps out two very different perspectives on the American Dream. One, Herschel’s, is comprised of a more idealistic, unbridled vision of hard working to live. Live for one’s family and community. The other, Ben’s, contains a more muddled, watered down version more akin to a societal expectation, one of living to work.

An American Pickle is a heartwarming story that is propped up by its thoughtful execution of the effects of diaspora on a family over the course of three generations, with this multigenerational perspective further nuanced through accurate historical references. This universally relatable film is less of a comedy than it is a meditation on finding one’s roots – after they’ve been ripped apart and scattered over the course of history and their ancestral memory – in an increasingly isolating America.