[dropcap]I[/dropcap] was recently in Philadelphia for a conference, and I had some free time on Sunday morning. For me, it was the perfect opportunity to go and visit the Philadelphia Art Museum. At $13, I thought a student ticket was pretty reasonable, especially taking into consideration the sheer size of the institution, yet, once I reached the register to pay for my ticket, I was surprised to find that the first Sunday of each month is classified as “pay as you’re able.”

It’s obviously not a new phenomenon. Every first Friday of the month at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery is pay as you’re able for the special exhibition, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art is famous for its long-respected use of this tradition for New York state residents. In my mind, it’s a wonderful policy, providing access to the arts for a wide variety of patrons. However, it’s not the easiest financial move for art institutions themselves. The Metropolitan Museum of Art used to be “pay as you’re able” for all visitors, but in 2018, it shifted its admissions policies to include full price tickets for non-New York state residents (though it honors this admission for three days after purchase). It represents a distinctly unstable model, and while many patrons offer a reasonable donation for their visits, that is something that can’t be depended on, nor should it be.

Making this decision even more difficult financially is the National Endowment for the Arts’ status within the United States government. The NEA began in 1965. The beginning of the legislation creating the endowment reads as follows:

Congress finds and declares the following:

1. The arts and the humanities belong to all the people of the United States.

2. The encouragement and support of national progress and scholarship in the humanities and the arts, while primarily a matter for private and local initiative, are also appropriate matters of concern to the Federal Government.

Today, the National Endowment for the Arts is constantly being put on the chopping block when it comes to federal funding. Announcements circulated in 2017 about cutting the NEA’s funding, and while the portion of the federal budget dedicated to it has risen in the last two years, it has not increased enough to compensate for the change in inflation over time. Now, the organization worries that this cut may come to fruition as President Trump and the Republican Congress shifts away from supporting the arts.

Today, the National Endowment for the Arts is constantly being put on the chopping block when it comes to federal funding. Announcements circulated in 2017 about cutting the NEA’s funding, and while the portion of the federal budget dedicated to it has risen in the last two years, it has not increased enough to compensate for the change in inflation over time. Now, the organization worries that this cut may come to fruition as President Trump and the Republican Congress shifts away from supporting the arts.

The NEA Chairman Jane Chu released a statement following the announcement of the NEA’s cut from the 2019 fiscal year budget:

“Today we learned that the President’s FY 2019 budget proposes elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts. We are disappointed because we see our funding actively making a difference with individuals in thousands of communities and in every Congressional District in the nation[…]As a federal government agency, the NEA cannot engage in advocacy, either directly or indirectly. We will, however, continue our practice of educating about the NEA’s vital role in serving our nation’s communities.”

There are two important parts of this statement. The first is obvious: the NEA is being cut. The second is the fact that it is a governmental agency and therefore cannot advocate for itself, and so individuals and institutions are left to lobby for its continuance. Personally, as a strong supporter of the arts, I would have a very difficult time not being able to advocate for my organization were it to be facing such a trial from the U.S. government.

Let’s Return to the Legislation Creating the NEA for A Second:

“The practice of art and the study of the humanities require constant dedication and devotion. While no government can call a great artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and inquiry but also the material conditions facilitating the release of this creative talent.”

It’s scary to think that we’re willing to forget the foundation of such a great organization. Right now, the National Endowment for the Arts takes up only .003% of the federal government. Additionally, according to Americans for the Arts, which is an organization dedicated to arts and arts education, the NEA budget amounts to only forty-six cents per capita.

It’s a small price to pay, I think, for an institution that has provided so much support for institutions and individuals across the nation. The American Academy of Poets noted that it is the only financial supporter that affects all 50 states. Furthermore, it is the “largest single funder of the arts across America.” While it does not cover all expenses of arts organizations, it is critical to their continued experience. The NEA removes pressures from these institutions so that they can be more accessible to the public.

It seems silly to question the role of the arts, culture, and the humanities in the United States. All forty-four former presidents have a painted portrait that was commissioned. The United States celebrates poets and has a poet laureate (currently, it’s Tracy K. Smith, who is one of my personal faves).

We certainly seem to have appreciated the arts at one point. We knew the value and the cruciality of it to our culture and to our citizens.

Not only that, however, by the arts have had an incredibly positive effect on the economy. In a 2016 report from Americans for the Arts, the arts contributed $699 billion to the nation’s economy, which is more than the shares contributed by transportation, agriculture, or tourism.

It’s important to note that the end of the NEA isn’t the end of the world. Most institutions only receive 10% of their funding from the government, only 3% of which comes from the federal government. However, since its creation, the NEA has also given over $46 million to over three thousand individual writers through fellowships, per the American Academy of Poets.

We certainly seem to have appreciated the arts at one point. We knew the value and the cruciality of it to our culture and to our citizens.

One of my most influential professors has been a recipient of these grants. Now, she’s awaiting the release of her second novel. I can only imagine that my life has been touched by many other writers who have received funding from an organization once thought to be so vital to the nation.

The influence of the arts trickles down and incites passion in those that come into contact with many of the opportunities made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts. So much so that the federal government once decided it was necessary for it to be involved in the furthering of its endeavors, leading to the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. We used to believe in the power of the arts.

In the Words of Jeb Bartlett: “What’s Next?”

If admission prices rise, that accessibility will become more and more difficult to justify financially and less people will be able to view the great works of artists past and present.

Arts institutions will persist. They may resort to measures like those taken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the creation of new admissions policies. They may resort to increased prices for exhibitions. Individual artists will suffer. It’s hard enough for artists to break onto the scene with the limited resources available. This too will restrict access.

Arts institutions will persist. They may resort to measures like those taken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the creation of new admissions policies. They may resort to increased prices for exhibitions. Individual artists will suffer. It’s hard enough for artists to break onto the scene with the limited resources available. This too will restrict access.

The National Endowment for the Arts isn’t just about artists, after all. It’s about those that benefit from funding to the arts. If admission prices rise, that accessibility will become more and more difficult to justify financially and less people will be able to view the great works of artists past and present.

When I left the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the line for admission extended much farther than it had when I walked in, and I had already found myself amidst a crowd of people as I gathered in front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. I’ll leave you with an image I’m afraid of losing by cutting funding to the National Endowment for the Arts: that of a class of elementary school children gathered around a sculpture, asked “What did you see?”

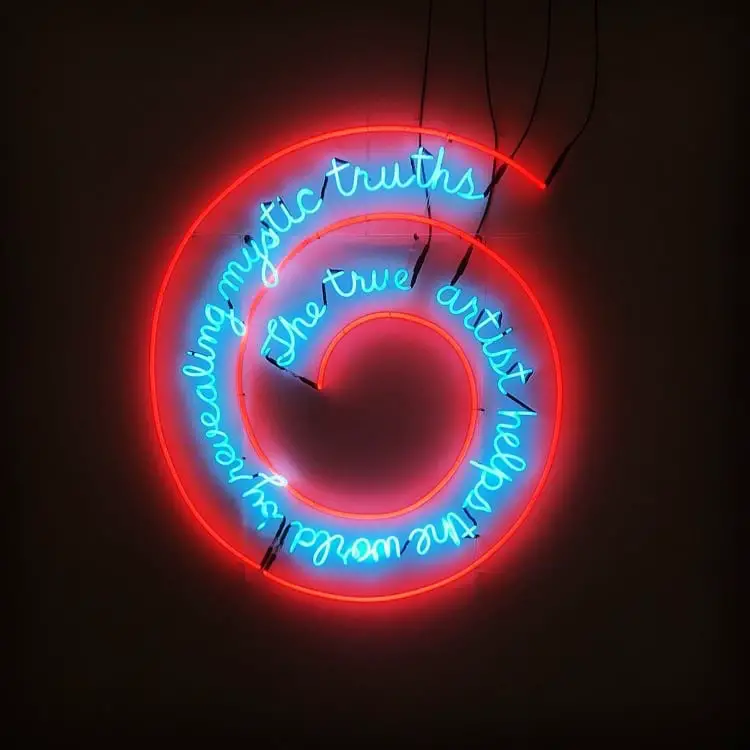

The featured image is of Bruce Nauman’s 1967 “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths,” housed at the Philadelphia Art Museum.