[dropcap]L[/dropcap]essons about screenwriting can be learnt from books, video courses, and live masterclasses, not to mention the practice of the craft itself. From my time studying the craft at university, I was disappointed to learn that the lecturers offered no original insight, no wonderful tips that would both enlighten and aid the constant struggle that is writing; they would regurgitate old methods and repeat themselves each year. I can understand the need for covering relevant material, but what if the students have already read the books they are teaching from: Campbell, Propp, Field, Yorke, Snyder, Vogler – all these brilliant minds have written exemplary books on the subject, but why spend $50,000 on a university course, when you could spend $7.99 on Amazon. The sad truth is that it all comes down to the certificate, and without that, apparently nothing else matters.

Nevertheless, this article is about those teachers that have stood out, that have challenged the norm, and made us question the basics and what we deem as fundamental. Highlighting what I think to be the most insightful tips on the craft of Screenwriting, I will list just a few, and hope that it will enlighten those who have reached a wall in their script or feel they need to make the hero/ heroine’s goal a little more challenging/relatable.

David Mamet

Take the first ten minutes of every movie and throw it away.

How do you make any movie better? Burn the first reel.

I’m in the middle of David Mamet’s Masterclass on masterclass.com, and I’m surprised to learn that in almost every lesson he teaches us to break at least one rule. It’s difficult to argue that he’s wrong when he has numerous achievements under his belt: Pulitzer Prize for Best Drama, Best Screenplay at Venice International Film Festival (which, FYI, is the oldest Film Festival in the world), and general international success as a writer.

Don’t write exposition and don’t write narration.

A piece of advice which stuck out to me was his segment on exposition and narration. What I hadn’t considered previously, was that the opening scene to most films is purely exposition. We are given a thorough breakdown of where we are, what we’re doing and endless mumbo jumbo of background information that will never make it into the film and is impossible to portray. In other words, it’s pointless, and I see that now.

Take the first ten minutes of every movie and throw it away.

Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross is a wonderful example of this – the script begins with:

SCENE ONE

A booth at a Chinese restaurant, Williamson and Levene are seated at the booth.

With no exposition other than a characters name and a general setting, we are thrusted into their conversation about ‘leads.’ Nobody knows what sales leads are, Mamet knew people wouldn’t understand and he put it in anyway. He says that you should start your story in the middle, whether it’s a conversation, a job, a hobby – let the audience figure out who the characters are and what they do by the clues you give them. Give the audience a chance to solve the puzzle – that’s where their involvement comes in. Exposition is information, and by handing too much information to the audience you are essentially giving the movie away.

A further example of where this has been used effectively is Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs.

INT. UNCLE BOB’S PANCAKE HOUSE – MORNING

Eight men dressed in BLACK SUITS, sit around a table at a breakfast cafe. They are MR. WHITE, MR. PINK, MR. BLUE, MR. BLONDE, MR. ORANGE, MR. BROWN, NICE GUY EDDIE CABOT, and the big boss, JOE CABOT. Most are finished eating and are enjoying coffee and conversation. Joe flips through a small address book. Mr. Pink is telling a long and involved story about Madonna.

We are only introduced to the characters by their names, nothing more. The conversation that then follows is just small talk to give the audience a taste of their personalities. Following on from a heated discussion about ‘Madonna’ and ‘Tipping’, we Cut To:

Over the BLACK we hear the sound of SOMEONE SCREAMING in agony. Under the screaming, we hear the sound of a car HAULING ASS, through traffic. Over the screams and the traffic noise, we hear SOMEBODY ELSE say:

SOMEBODY ELSE (OS)

Just hold on buddy boy.

SOMEBODY stops screaming long enough to say:

SOMEBODY (OS)

I’m sorry. I can’t believe she killed me. Who would’ve fuckin thought that?

If we consider the fact that this is already 5/6 pages into the script and we are still none the wiser as to who these people really are, what they do or what is happening, it leaves plenty of room for us as the audience to be more intrigued to both figure out what is going on and to think ahead.

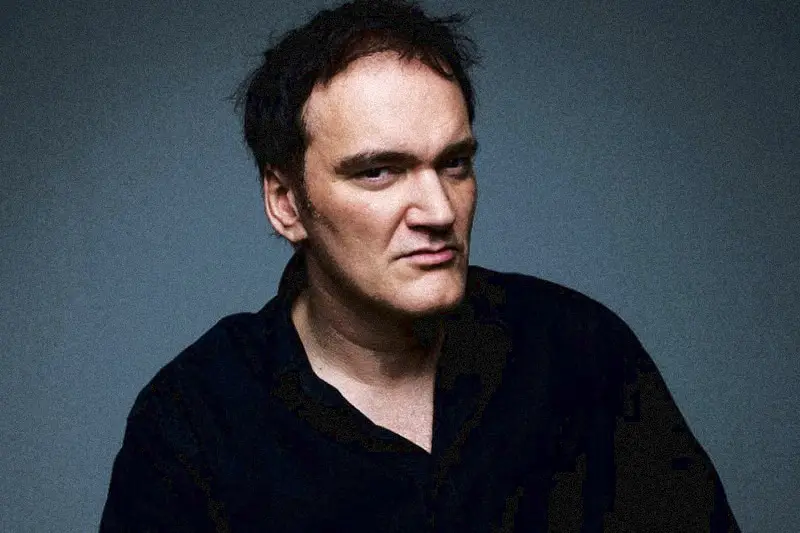

Quentin Tarantino

Speak of the devil; this would not be a true film students guide if we did not mention the most notable film student of all. Quentin Tarantino has prospered as one of the greatest auteur filmmakers of the 21st Century; his credits including: Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained and many more – all of which received critical acclaim for his screenwriting.

When people ask me if I went to Film School I tell them, no, I went to Films.

However, Tarantino does not have an overnight success story and rejection was a big part of his early career; writing agents turned down Natural Born Killers and True Romance before he had to rethink his approach and decided to go back to his apartment, write Reservoir Dogs and set out to film it himself. In other words, if one story doesn’t work out, write another one.

I steal from every movie ever made.

If we had to consider what Tarantino’s writing has taught us about style, it would be to immerse oneself within the genre they’re writing. His movies have been influenced by so many others: Tarantino’s 1992 film debut Reservoir Dogs to be largely informed by the Hong Kong crime film City on Fire, released five years earlier; he pays homage to one of his favorite directors, Sergio Leone, in Django Unchained with visual cues and dialogue, especially at the end where the hero rides off victorious as the antagonist is cut off and left behind to die; Pulp Fiction’s iconic bible passage which is delivered at the beginning of the 1973 Japanese film Karate Kiba; or lastly, the the final battle scene in Kill Bill, Vol. 1 to be lifted from the 1980 Italian horror film City of the Living Dead. The influence of other filmmakers is undoubtedly one of the most important aspects to a writers toolkit.

If you just love movies enough, you can make a good one.

How has his writing allowed this development of style? Well, through the imitation of other writers, for instance he confesses that his character dialogue to be inherently influenced by David Mamet, and his approach to characters from the novelist Elmore Leonard; his writing is prolific and his dedication to the craft has formed a uniqueness in his work, his style is distinct and known worldwide but having a distinct voice does not come after your first script – a style needs to develop itself naturally, but more importantly it has to be practiced through more writing. Tarantino would be an advocate for ‘writing is key’, whatever it may be, write every day.

Aaron Sorkin

With a great script a Screenwriter’s ‘voice’ can transcend any actor or director and their script can have an equally powerful effect if it were made into a Podcast with no visuals whatsoever. This talent lends itself to only a few, but it can be taught and it can be practised. Two words… Aaron Sorkin.

Writing is like playing an instrument – the more you write, the better you’ll get.

We know Aaron Sorkin for his commercial success as the creator of The West Wing, The Social Network, and Steve Jobs. But his earlier career includes credits for stage plays, most notably, A Few Good Men – which Sorkin confesses to have written on cocktail napkins whilst he worked as a barman to pay his rent. Finishing a script is never easy, and although Sorkin’s scripts are always snappy and sharp, he’ll be the first to tell you that writing it is the complete opposite – it takes time, a lot of time.

Writer’s block is my default position.

His turnaround rate from idea to finished script is roughly two years. Two years sounds like a long time, which is because it is a long time, but when you consider that you are creating new worlds that hopefully absorb the audience, it’s best to be thorough.

Now begs the question, how does he prepare in those two years?…

Well, lets start with what he ranks as a priority when starting to write a script…

The most challenging thing about being a writer is that most days you don’t write.

I loved the sound of dialogue, it sounded like music to me.

A key feature of Sorkin’s writing, is his dialogue. Sorkin’s dialogue is unique, it’s memorable and expertly disguised as the way people really talk. When considering his ‘style’, he’s in leagues with Mamet, their writing is immediately recognizable – fast back-and-forth conversation, constant confrontation, and of course the pace of their stories are at the mercy of their dialogue.

The opening of Sorkin’s The Social Network:

FROM THE BLACK WE HEAR–

MARK (V.O.)

Did you know there are more people with genius IQ’s living in China than there are people of any kind living in the United States?

ERICA (V.O. )

That can’t be true.

MARK (V.O.)

It is true.

ERICA (V.O.)

What would account for that?

MARK (V.0.)

Well first of all, a lot of people live in China. But here’s my question:

FADE IN:

Interestingly, despite Sorkin’s films being dialogue heavy we are in constant suspense, surprised by the next scene and unable to see the ending until it hits you. A key part of this skill would be his ability to hide exposition within his dialogue. Exposition is the art of giving information, but with Sorkin’s films we don’t know even we are being fed it – this is otherwise known as ‘exposition without desire.’

Plot and structure is like a necessary intrusion on what we really want to do, write dialogue.

But wait, here comes the shocker, Aaron Sorkin himself tells us that despite his love for dialogue, it ranks the least important element in his scripts, and so should it in yours.

I worship at the altar of intention and obstacle.

Intention and Obstacle are everything. What does the Protagonist want and what’s standing in their way? Dialogue comes last because unless there is a plot, dialogue has no place to go. Dialogue is simply a tool to communicate with conflicting characters and ultimately create drama in a scene. But in order to have drama, there needs to be a conflict; so for example, if there are only two people in a room, make them disagree on something – who wants what and what’s standing in their way – only then do we have drama.

Many stories I’ve either written or have begun writing, I’ve doubted the strength of my Intention and Obstacle, whether my Intention is solid enough to carry my characters through the journey and still be interesting. Sorkin’s advice to this is to write your characters intention as if “they are making their case to God why they should be allowed into heaven.” In other words, your characters must be so obsessed with their Intention that they’ll think of everything and stop at nothing to achieve their goal (but, FYI, failure is an option, they just need to have tried – this would be a ‘tragedy’ as opposed to a ‘comedy’).