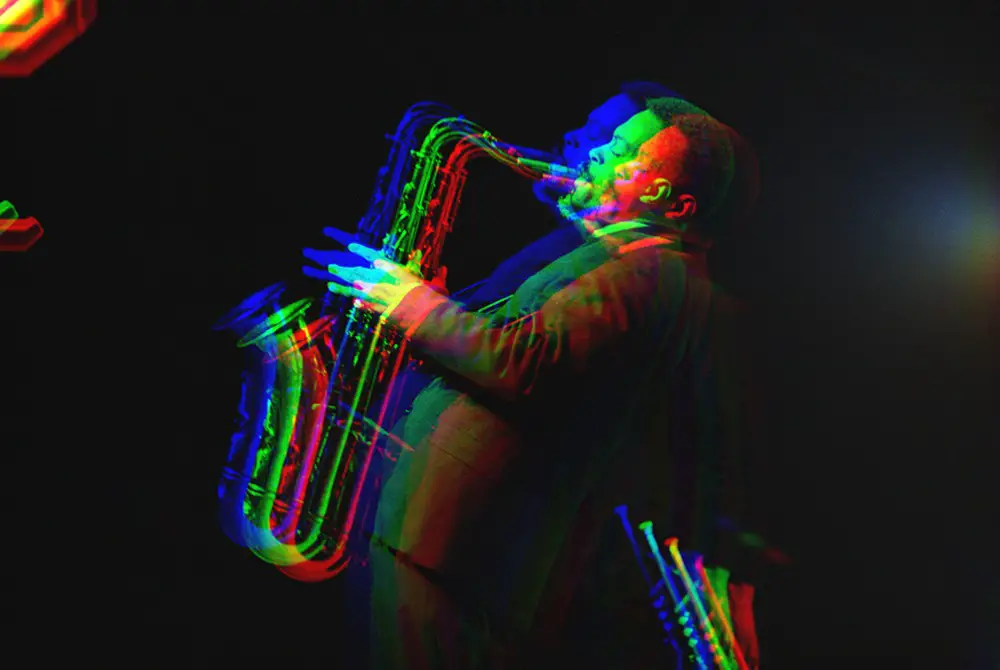

[dropcap size=big]M[/dropcap]aybe tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler spoke those words, maybe he never did. But he certainly did say exactly that with his music, music that was at the same time categorized as free jazz, spiritual jazz, even folk jazz. It was certainly music that inspired musicians past (legends like John Coltrane and Archie Shepp), and present, guitarist Marc Ribot recently did a complete remake of Ayler’s seminal Spiritual Unity album, and British rising sax player Shabaka Hutchings naming the same album as ‘life-changing.’

Still, that was not enough for Ayler to get the wider recognition he truly deserved. Not even a couple of rock and beat infused albums at the turn of the ’60s and ’70s could help. Not even a single Ayler sample is to be found.

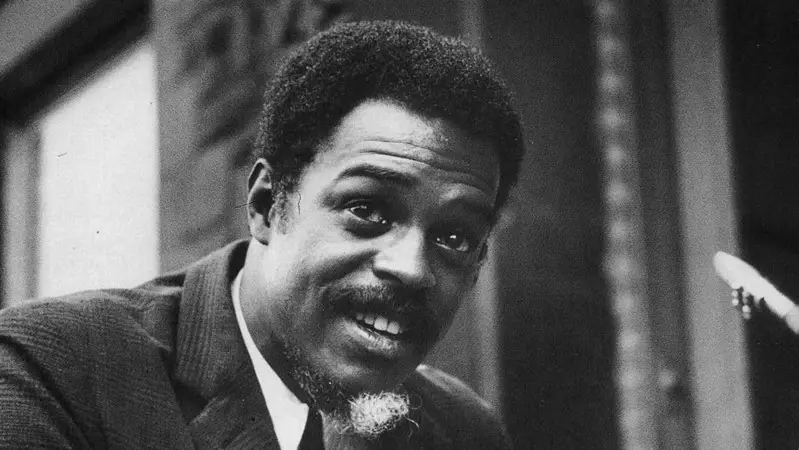

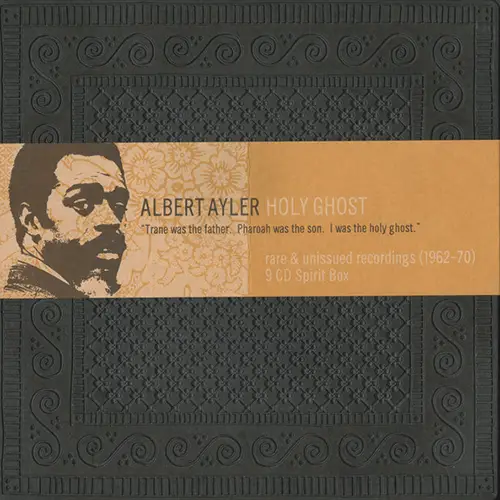

Actually, even at his prime, Ayler was a contested topic in jazz and music circles in general, where even LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), initially a big supporter, derided Ayler’s later output. Not even the lavish box set released in 2004 (Holy Ghost, Revenant Records) helped. Don’t look for it unless you want to fork out over $175, it is out of print.

A Man with Music in His Head, the Spirit in His Heart, Ghost Over His Head, and Constant Poverty

Ayler took up the saxophone at an early age back in Cleveland, where he was born, thanks to his father, a semi-professional musician, who was also his first teacher. Through various gigs, he ended up with Little Walter’s R&B band, where he got a nickname ‘Little Bird’, as his strong, vibrant tone reminded the name-givers of Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker.

…two, three years since Ornette Coleman started re-shaping jazz, Ayler’s musical concepts seemed to be too free for the then jazz scene…

Interestingly enough, at approximately the same time, Ayler became a junior golf champion at a time when the sport was not exactly welcoming people from Cleveland Heights with open arms. He never stuck at it, and he might have been better off financially, but who knows where his spirit would have gone.

Ayler started his college studies but had to quit because of lack of money, so he joined the army and landed in a military band stationed in Europe. Thinking he earned enough and already with his own musical ideas in mind, he quit the army in 1961, moving back to the US. And although it was already two, three years since Ornette Coleman started re-shaping jazz, Ayler’s musical concepts seemed to be too free for the then jazz scene, so he moved back to Europe, settling first in Sweden in 1962, where he recorded with Don Cherry, a like-minded, world music-inspired musician and then joined another free jazz initiator and legend Cecil Taylor.

The music he is trying to get together,” Jones wrote, “is among the most exciting – even frightening – music I have ever heard… The sound is fantastic. It leaps at you, actually assails you, and the tenorist never lets up for a second. The timbre of his horn is so broad and gritty it sometimes sounds like an electronic foghorn… everybody playing tenor had better watch out. ( LeRoi Jones, Downbeat, February 1964)

As it seemed to be something that followed Ayler throughout his short life, he was always a bit too far ahead of everybody else, since his initial Swedish recordings were only to be released years later. His formal debut, My Name Is Albert Ayler was recorded in Denmark a year later and already gave a peek at what Ayler was ready to unleash – a free-form musical exploration that went beyond the boundaries of jazz or any other music that included everything he experienced musically – from church spirituals, New Orleans and Army brass music, to world folk forms, to free improvisation – any and all of these themes, often all at the same time.

Albert Ayler as Inspiration and as a Threat

…Ayler’s music was ‘threatening’ in many ways, it was incendiary, it was fire music, something that should not only be avoided but completely erased.

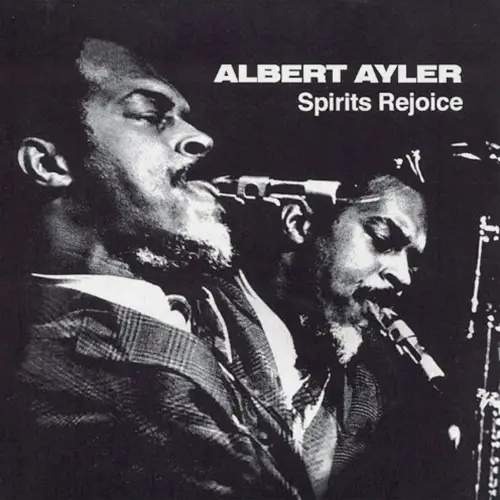

With his following works, particularly Spirits, Ghosts, Spirits Rejoice, and particularly Spiritual Unity, one of the most crucial pieces of jazz music, Ayler presented his key intention and that was to create something spiritual in the sense of universal, as something that can unconsciously reach a higher plane. As far as fellow musicians like Coltrane and Shepp, as well as others and a handful of music critics are concerned, Albert Ayler ushered a new era in jazz, so much so that both Coltrane and Shepp cited him as somebody who changed their perception and approach to music. Actually, Coltrane became one of Ayler’s key supporters, not only morally but financially, with Ayler’s personal downfall taking a rapid course after Coltrane’s death in 1967.

The problems Ayler encountered in his acceptance lay much deeper than can be only tied to ‘musical differences.’ As Pitchfork contributor Mark Richardson points out: “the sound and style of free jazz were closely identified with the black liberation movement, serving as both a metaphor— a culture that breaks free of oppressive structure—and, through its sound, a direct expression of pain, anger, and redemption… free jazz forced listeners to reckon with fundamental questions about the nature of music itself.”

“And it wasn’t about the harmony or the specific notes, it was just sort of a texture…But this was untranscribable – it seemed like there was nothing to steal from it.” (Shabaka Richards on Ayler’s Spiritual Unity Album)

So, Ayler’s music was ‘threatening’ in many ways, it was incendiary, it was fire music, something that should not only be avoided but completely erased. And that is actually what really happened, at least one one known instance – as the famous jazz critic Richard Williams writes in his Ayler appreciation in Guardian, in November 1967 Ayler’s quintet played his only London performance and the only one before the cameras, at the London School of Economics. The concert was recorded for the BBC2 series “Jazz Goes to College.” But not only were the tapes abandoned and never aired, but they were simply erased.

“On your way down”

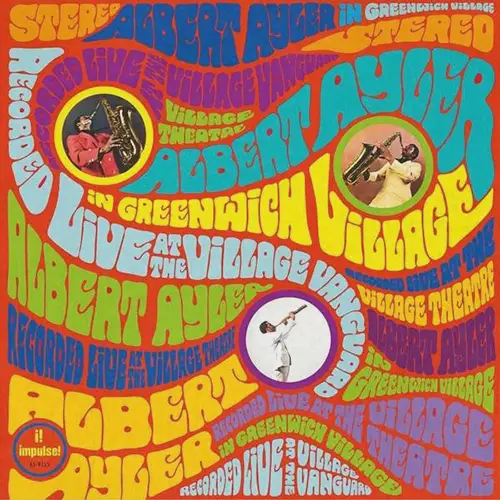

The title of this Little Feat song (a band whose destiny shares a few similarities with Ayler’s) doesn’t describe Albert Ayler’s path in full. The problem was that, unfortunately, Ayler never truly got up where he belonged. Although his premature death came about in late 1970, Ayler’s true demise started with John Coltrane’s death in 1967. Coltrane was not only financially supporting Ayler, but he also secured him his only ’stable’ recording deal with Impulse! Records, with the live album In Greenwich Village, one of Ayler’s key works and one of the key live albums in any genre coming the same year as Coltrane’s death.

One of Coltrane’s last requests was that Ayler and Ornette Coleman play at his funeral. Among the themes Ayler played was “Our Prayer,” one of his seminal recordings (composed by his brother Donald), when at the end of his solo Ayler stopped playing his instrument and started uttering wordless screams within the church.

…Ayler’s true demise started with John Coltrane’s death in 1967. Coltrane was not only financially supporting Ayler, but he also secured him his only ’stable’ recording deal with Impulse! Records…

From there on, things got only worse. Ayler was pressured by Impulse! to record more ‘approachable’ music (still miles away from anything commercial though), and he started behaving erratically, accusing the then in vogue singer Tom Jones of stealing his music in a TV interview, and people reporting that he was walking with a fur coat and gloves on, covered in Vaseline during summer months.

It all ended in mystery when his body was found in the river in Brooklyn at the end of November 1970. And although it was initially proclaimed that he drowned, later on, it was discovered that there were possibly stab wounds all over his body, marking his death a mystery to this day.

While recording The Beach Boys never-released epic Smile back in 1967, Brian Wilson proclaimed that he was creating ‘teenage symphonies to God.’ Albert Ayler’s music may certainly not be called teenage, but can certainly fall into the category of symphonies to God. Played with fire.