[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]alk Through British Art, the permanent exhibition at London’s Tate Britain, is also a walk through British music. Peter Lely’s portrait of Two Ladies of the Lake Family (c. 1660) has a highly detailed guitar at its center, an instrument that was becoming fashionable in the English court at the time. The carelessly strewn instruments in Edward Collier’s Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’ (c. 1696) juxtaposes the inevitability of death with the fleeting pleasures of wine, jewels, and music. Marcellus Laroon’s A Musical Assembly (c. 1720) is alive with the energy of the actors and painters of early eighteenth-century Covent Garden.

Each, in its own way, invited me to wonder not only what the painter saw, but what they heard…

What struck me as I admired these depictions of music-making was the silence in the gallery. Each, in its own way, invited me to wonder not only what the painter saw, but what they heard, and none more so than Martin Ferdinand Quadal’s Portrait of a Man Playing a Flute (c. 1777): depicted with eyes closed, potentially to convey the blindness of the subject, the effect is an intimate and beguiling moment of performance that left me longing to hear his music.

1540-1810

In the first room of the exhibition, the bright and vibrant portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (c. 1563) drew my attention immediately: a keen musician herself, as well as an ardent admirer of music, Elizabeth’s reign was both a literary and musical golden age in England. Whilst marveling at this huge, almost glowing portrait, I listened to a recent recording of William Byrd’s “Terra tremuit” – part of a series of Latin motets written for the queen – and wondered how she might have felt whilst listening to this piece 450 years ago.

I listened to a recent recording of William Byrd’s “Terra tremuit” – part of a series of Latin motets written for the queen – and wondered how she might have felt whilst listening to this piece 450 years ago.

The early eighteenth century was dominated by the German-born Londoner George Frideric Handel; the debut of his famous Water Music, performed for the king on barges sailing up and down the Thames, is a legendary part of London’s musical history. This period was also the age of the harpsichord, a precursor to the piano: Handel’s “Air”, from his “Suite No. 3 in D Minor” (HWV 428) made an arresting accompaniment to the numerous and varied portraits of the eighteenth-century elite, a personal favorite being Michael Dahl’s dramatic portrait of Mrs Haire (c. 1701). One painting that writes its own soundtrack is William Hogarth’s A Scene from The Beggar’s Opera (c. 1731), a satirical ballad opera written by John Gay. Widely considered to be a forerunner of modern musical theatre, Hogarth captures the immersive vibrancy of the theatre.

1810-1930

The Victorian era in Britain saw a conflict between modern tastes and antiquity in theatre, architecture and music: Edward Francis Burney’s Amateurs of Tye-Wig Music (c. 1820) depicts the tension between contemporary composers like Beethoven and Mozart, and the older compositions of Handel. The lively landscapes of Constable and Turner reflect the fusion of traditional Britain and avant-garde style: Constable’s melancholy sketch for Hadleigh Castle (c. 1828-9) comes to life with John Field’s stirring “Nocturne No. 2 in C Minor.”

Constable’s melancholy sketch for Hadleigh Castle (c. 1828-9) comes to life with John Field’s stirring “Nocturne No. 2 in C Minor.”

The title of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea (c. 1871) implies a forward-thinking approach to the relationship between music and art. The painting brought to mind the jazz standard “Chelsea Bridge”, written by Billy Strayhorn around 1941 and most famously played by Ben Webster. Though an anachronistic match, Strayhorn had a unique perspective on music in relation to other art forms, which seems to echo Whistler’s work. It is also believed that Strayhorn’s composition was inspired by a painting by Turner or Whistler of Battersea Bridge: standing in front of this delicate landscape, I couldn’t help but convince myself it was this one. Against the smooth sound of Webster, the tragic heroines depicted in many other paintings in the room – masterpieces by the likes of John Everett Millais, John William Waterhouse, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti – recalled the tragic heroines of jazz who now have an equal place in modern mythology.

The portrait of Ena and Betty Wertheimer (c. 1901) by John Singer Sargent is relaxed and likeable: the personality of Ena radiates from the canvas, and the depth of color and texture in their modern gowns looks good enough to touch. The portrait, particularly the depiction of Betty, is reminiscent of Sargent’s Madame X (c. 1884), a painting of an American expat that shocked Paris high society and now hangs in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s not difficult to imagine these two affluent, modern women embracing the American musical developments of ragtime and jazz that would cross the Atlantic in the following decade.

…it is not difficult to imagine these cinema-goers springing out of their seats and dancing to “Clarinet Marmalade.”

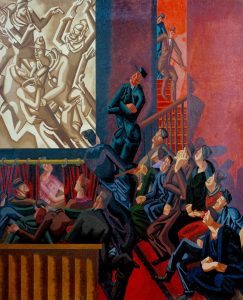

In the next room, there is an unavoidable Transatlantic influence, most obviously in Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson’s The Arrival (c. 1913). William Roberts’ The Cinema (c. 1920) illustrates the dynamic impact of Hollywood film in Britain: the audience is the real subject of this painting, with figures running down the stairs like slapstick stars, a couple embracing like romantic heroes, shadows bouncing euphemistically from each form, and an almost hidden pianist playing an expressive accompaniment lost in time. The 1919 British tour of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band is widely credited as the beginning of jazz in Britain: it is not difficult to imagine these cinema-goers springing out of their seats and dancing to “Clarinet Marmalade.”

1930-1970

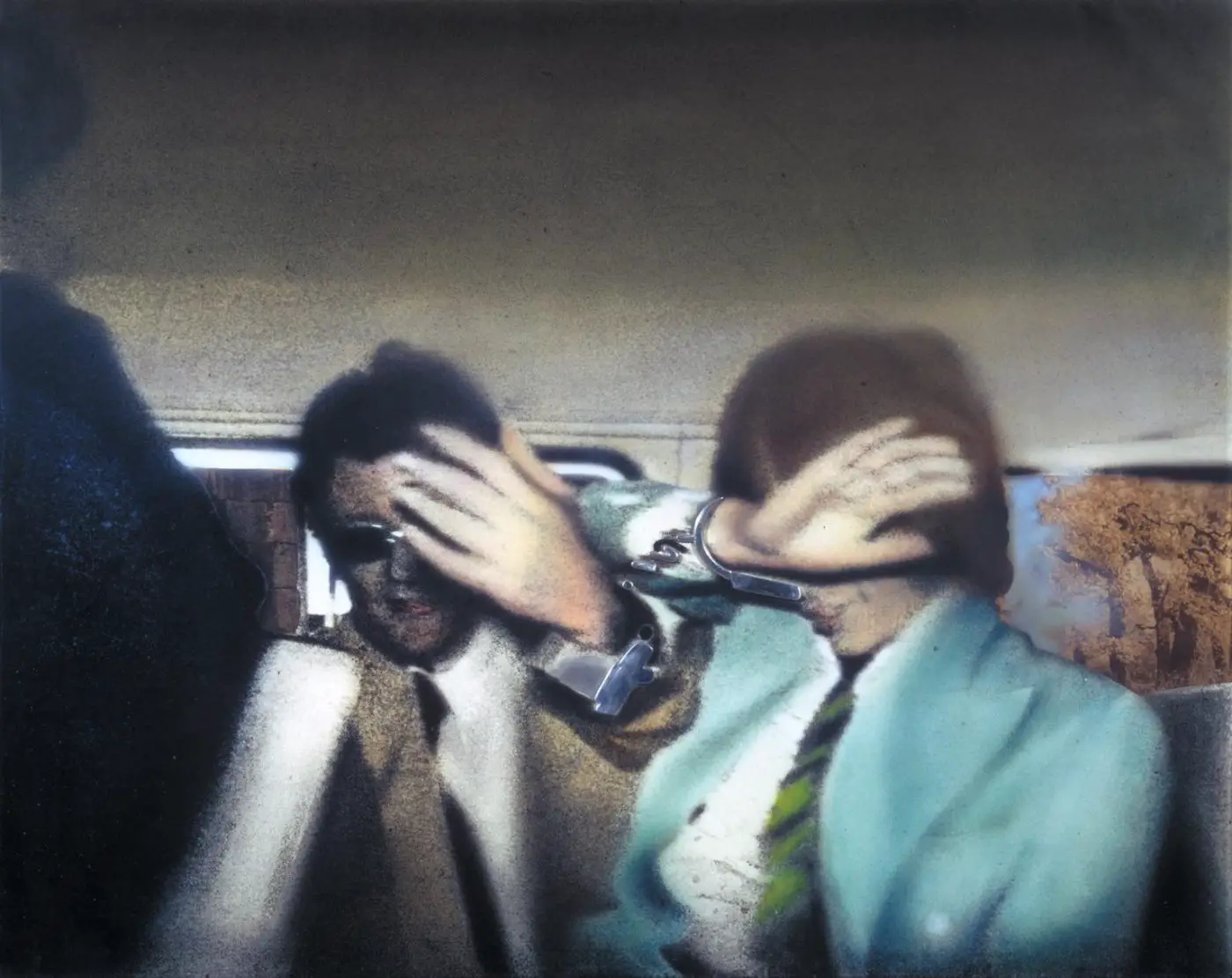

The works from the post-war period were markedly devoid of music. Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (c. 1944) is so viscerally painful that I found it rejected any attempt to unpick it using music. The succeeding mix of social realism and high abstraction was similarly alienating: it was not until I reached the vibrant world of David Hockney and Peter Blake that music re-emerged in the artworks. British pop iconography was suddenly strongly present: Richard Hamilton’s 2007 collage celebrating The Beatles served as a reminder of Britain’s dominant popular music legacy, and Jamie Reid’s ‘No Feelings’ (1977), in a style instantly recognizable from the album artwork of The Sex Pistols, emphasized the ever-growing importance of counterculture in British artistic history. It was Hamilton’s repurposed photograph of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser in Swingeing London 67 (f) (1968) that I found to be the most evocative: not only did the work immediately recall The Rolling Stones’ hits like “Ruby Tuesday” from the late 1960s, but it bursts with questions about celebrity culture, the transience of youth, and the idea of the ‘image’ itself. It was also an apt symbol for my project: music and art literally handcuffed together.

…not only did the work immediately recall The Rolling Stones’ hits like “Ruby Tuesday” from the late 1960s, but it bursts with questions about celebrity culture, the transience of youth, and the idea of the ‘image’ itself.

1970-Today

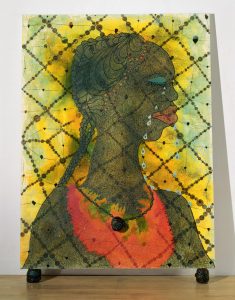

Though the 1970s and 1980s were artistically formative, the next piece that really caught my attention was No Woman, No Cry (1998): Chris Ofili’s striking tribute to Stephen Lawrence, a teenager murdered in an unprovoked racist attack in London in 1993. Though it has an unavoidable musical connection in its title, I felt that Dizzee Rascal’s “Sittin’ Here” was an apt contemporary match; the speaker’s frustration with London life gives a voice to an endangered generation, a context enhanced by other pieces in this collection.

…Dizzee Rascal’s “Sittin’ Here” was an apt contemporary match; the speaker’s frustration with London life gives a voice to an endangered generation…

The most recent work currently in this exhibition, Marlene Dumas’ portraits of the esteemed nineteenth-century writer Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas ‘Bosie’ (c. 2016), are particularly touching. The romantic relationship between Wilde and Bosie, at a time when homosexuality was illegal in the UK, led to Wilde’s harsh imprisonment and eventual death. The portraits brought to mind Irish musician Hozier’s 2013 single “Take Me to Church”, an emotional protest against the Catholic Church’s stance on homosexuality. In the knowledge that Ireland, Wilde’s home country, became the first country to legalize gay marriage on the basis of popular vote, the sight of the portraits together was bittersweet.

From Elizabeth I to Stephen Lawrence, adding music allowed me to connect with artworks that may have otherwise felt distant. Music pours silently from the paintings in this collection, and I found reuniting these different forms of artistic expression to be a thrilling experience.