[dropcap]P[/dropcap]icture yourself standing in an art gallery. You see rows of canvasses decorating the walls, tourists looking at smartphones pointed at paintings, stewards sitting lifelessly under the luminous fluorescent lighting. But what do you hear? Though your answer is most likely nothing (the clicking of cameras and buzzing of visitors excepted), that could soon change. Imagine the same gallery, but with Beethoven’s seventh, or Kind of Blue, or Kendrick Lamar echoing in your ears. What impact could a curated playlist of music have on the way viewers perceive an art exhibition? Whether intended to provide historical or artistic context, or as an abstract statement on the cross-genre interaction between visual and aural art, music could be the key to unlocking a more visceral, multi-sensory approach to art viewing and creation. The increasing use of various digital media already hints at a radically new way of exploring museums and galleries: it is time for curators to face the music and embrace the artistic potential of playlists.

Whether intended to provide historical or artistic context, or as an abstract statement on the cross-genre interaction between visual and aural art, music could be the key to unlocking a more visceral, multi-sensory approach to painting.

Matisse, Mondrian and Thelonious Monk

Tate, the UK art institution that houses the national collection of British art, is beginning to incorporate curated Spotify playlists into its exhibitions. The playlists – available on Spotify – currently include soundtracks for a number of significant twentieth-century artists, including Henri Matisse, Andy Warhol and Piet Mondrian. Alan Scholefield, the curator of the ‘Sound of Matisse’ playlist, aimed to “allow music to intrude from unexpected places into the magical world of Matisse’s art, and so to provide a score of sorts for the dance of Matisse’s ‘carving into colour’”. For an artist so heavily influenced by music, pairing the colourful collages with bebop and Thelonious Monk is more of a reunion than a mismatched artistic intrusion. Similarly, the tracks that encompass the sound of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian are selected from his record collection, and include a classic Charleston as well as jazz standards from Ellington and Armstrong. Listening to the comforting tones of Louis Armstrong on ‘When You’re Smiling’ doesn’t quite reflect the tone of Mondrian’s work, but softens the cold and brash aesthetic of boxy monochrome and primary colours. It also serves as a helpful reminder of Mondrian’s forward-thinking approach to art: he was producing pieces that would not look out of place in contemporary galleries before Gershwin had rhythm or Ellington had swing.

The experience of viewing a collection of Andy Warhol’s art would be different if you listened to Jon Davies’ 21st-century ‘underground’ playlist, which engages with Warhol’s ability to “kick against contemporary hierarchy between high and low culture”…

Another angle is provided by the playlist for the British painter L.S. Lowry, who is famous for painting life in the industrial North of England. Rather than try and resurrect the sounds of Lowry’s life, the playlist features some of the most distinctively Northern music of the past fifty years, from the likes of Oasis, The Smiths, Happy Mondays and punk poet John Cooper Clarke. For some artists, alternative playlists emphasize particular themes within their work. The experience of viewing a collection of Andy Warhol’s art would be different if you listened to Jon Davies’ 21st-century ‘underground’ playlist, which engages with Warhol’s ability to “kick against contemporary hierarchy between high and low culture”, or a playlist featuring Warhol’s musical contemporaries such as the David Bowie, Blondie and The Ramones. Warhol’s status as an artist who experimented with different media, such as his series of multimedia events called Exploding Plastic Inevitable (featuring performances by The Velvet Underground and Nico alongside dance, performative painting and screenings of his films), should encourage curators to play with the artistic possibilities of curating music to accompany his works.

Sound of a Nation

It is intriguing to imagine that someone standing next to me, viewing the same painting, could have a totally different perception of it depending on the song they had landed on: how the way I viewed the murals on the Wall of Respect in Chicago, for example, might have varied if they were listening to Nina Simone’s ‘I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free’ or Elaine Brown’s ‘Seize the Time’.

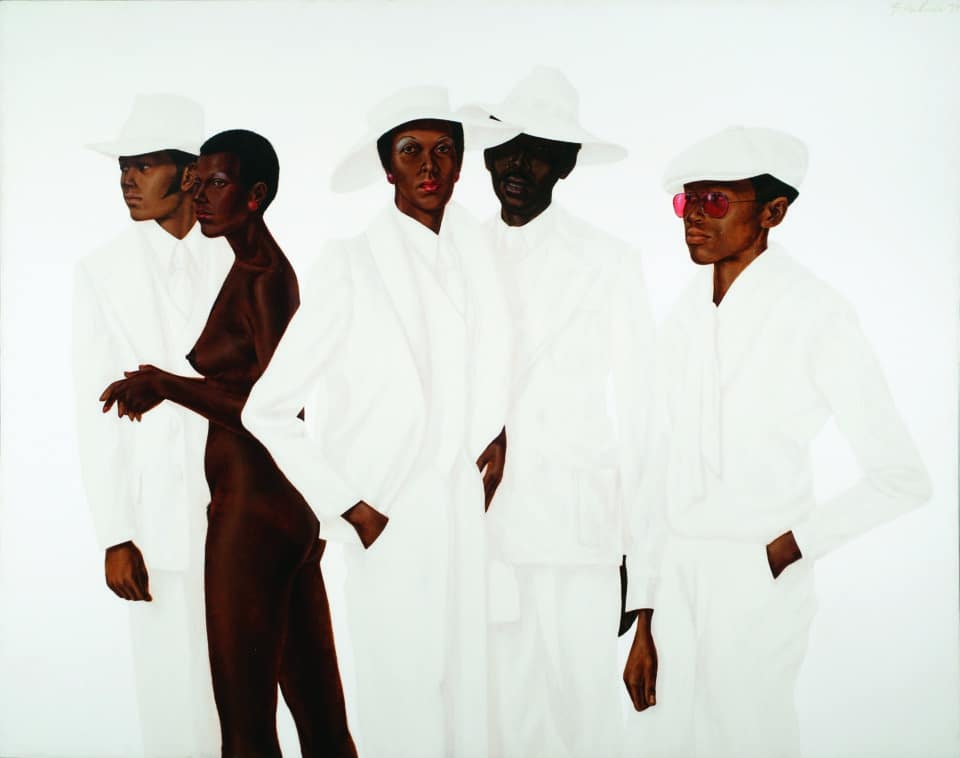

A current exhibition in London’s Tate Modern, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, showcases the indispensable contribution of Black artists to American art and history. Opening in 1963, it is difficult to see how the art of this period of political turbulence could be accurately depicted without appealing to the contemporaneous music, from Miles Davis to Marvin Gaye (and the rich variety in between). A Spotify code, which visitors can scan with their smartphones to access the playlist, adorns the wall at the opening of the exhibition, an abstract visual representation, in itself, of the music that this technology unlocks. Though the curator’s intentions for the playlist can be found online – which songs were meant for which room and the reasons for the pairings – most visitors who I saw use the playlist appeared to view the exhibition more organically, allowing the music and visual art to coordinate according to viewing pace rather than the curator’s guidelines. It is intriguing to imagine that someone standing next to me, viewing the same painting, could have a totally different perception of it depending on the song they had landed on: how the way I viewed the murals on the Wall of Respect in Chicago, for example, might have varied if they were listening to Nina Simone’s ‘I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free’ or Elaine Brown’s ‘Seize the Time’. For me, the overwhelming vibrancy of William T. Williams’ abstract masterpiece Trane came to life with synaesthetic vitality when paired with Duke Ellington’s ‘Fleurette Africaine’. Romare Bearden’s gritty collages became unsettling when Charles Mingus’ ‘Original Faubus Fables’ echoing in my ears. The figures in Barkley L. Hendricks’ strikingly beautiful study What’s Going On? were a delicate embodiment of Marvin Gaye’s iconic tune of the same name. I saw the man in Benny Andrews’ 3D piece Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree? literally bulging out of the canvas as if he had been animated by Gil Scott-Heron’s command that “the revolution will not be televised… the revolution will be live”.

Appealing to people’s love of music might be a way of attracting new visitors to art galleries, and making a sophisticated and imaginative interaction with art more accessible. Perhaps, in this age of cinema, we yearn for multi-sensory artistic experiences: videos with our music and music with our images. Innovative exhibitions in the UK, the US and elsewhere are acknowledging the power of combining music and visual art, and utilizing the widespread use of smartphones and apps like Spotify to innovate without excluding those attached to the art gallery as a space for silence. As a passionate advocate of multi-sensory creativity, a more holistic approach to art galleries is music to my ears.

Featured Image: https://www.999club.org/happy-anniversary-999-club/